Monopolies: The game that goes on

The ‘Curse of bigness’ is back: wealth and power are once more concentrated in just a handful of companies [1].

President Theodore Roosevelt was hailed for dismantling the powerful monopolies which emerged from America’s industrial revolution. Does his trustbusting provide a blueprint for what investors can expect from a revitalised antitrust movement on Capitol Hill?

It rips through families, pitting brother against mother. It enrichens a lucky few whilst turning most into penniless jailbirds. And yet you’ll gladly fetch it out of the cupboard each Christmas.

The game of Monopoly was created by Charles Darrow. After losing his job selling domestic heaters during the Great Depression, Darrow translated the booms and busts of the US real estate market into the board game we know today. Monopoly made him a millionaire, an incarnation of the American Dream.

Or so the story goes.

But, like many great stories, it isn’t exactly true [2].

In 1904, Elizabeth Magie – a writer and women’s rights advocate – filed a patent for The Landlord’s Game. It was designed to promote the ideas of political economist Henry George. His seminal work, Progress And Poverty, argued for a single tax on the value of land and other antimonopoly reforms to reverse deepening social inequality.

Here’s the twist. Magie created two sets of rules for The Landlord’s Game. In one, the monopolist could crush opponents. In the other, wealth was spread more equally between players and the winner could claim only a marginal victory.

Darrow – as you know – adapted the first set of rules when creating Monopoly.

THE SPIRIT OF THE AGE

The Landlord’s Game was born at the height of the ‘Trustbusting’ era in the early 20th Century, when the debate about monopoly power had come to dominate corporate America.

Monopolies seldom come about by accident.

Wealth and power were concentrated in the hands of a few successful businesses. So-called ‘Trusts’ (the legal term for corporate groups exercising significant control over a specific product or industry) simultaneously propelled and engulfed the United States’ economic growth. This was the conundrum that confronted policymakers – was monopoly the essential and inevitable end state of successful business? What of competition, or its absence? And how could the trusts be broken up whilst still championing growth?

It is a debate we recognise today. Big tech, big pharma and big banks find themselves in the crosshairs of an emboldened antitrust movement in Washington. So can any lessons be learnt from the trustbusters of yore?

TO THE VICTOR GO THE SPOILS

In the later 19th Century, the US economy grew at a scintillating rate. Rapid industrialisation was accompanied by sophisticated financial innovation. Railroads steamed across state lines, barrels of oil rolled through the country and the shipping industry grew at a rate of knots.

Soon, winners emerged. Carnegie, Vanderbilt, Gould, Morgan, Rockefeller were the opportunists of the Gilded Age, a rollcall of robber barons – eponyms of the streets, train stations and concert halls of America.

Monopolies seldom come about by accident. The trusts dominated markets by keeping prices low when competitors appeared. They actively pursued monopoly power by vertical integration – combining the businesses that operate at different stages of production into one conglomerate.

The trusts grew four times faster than more competitive sectors [3]. And yet the political will to curtail these corporate behemoths waxed and waned.

John D Rockefeller was initially lauded for improving industrial efficiency and lowering the price of kerosene. He merged more than 100 oil refineries into his Standard Oil trust – which by 1901 controlled 91% of US oil production [4].

Between 1897 and 1901, more than 2,000 mergers took place in the United States [5]. No period in American history has witnessed a more significant consolidation of economic activity than this ‘Great Merger Wave’ [6].

A small number of trusts came to wield absolute control over the steel, meat packing, sugar refining and tobacco industries.

Come the turn of the century, the tentacles of the trusts enveloped the nation. Small business owners, factory workers and consumers began to buckle under the weight of the new great powers. Americans wanted someone to fight the trusts, and it was a fighter they got.

SPEAK SOFTLY AND CARRY A BIG STICK

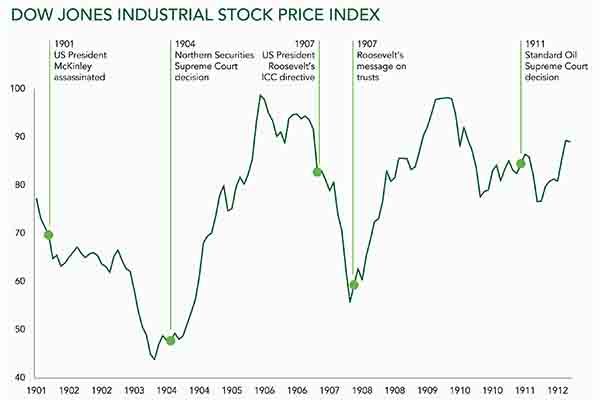

In September 1901, President William McKinley [pictured above] was shot by a young steelworker, Leon Czolgosz. On the days of McKinley’s shooting and his death the following week, the Dow Jones Industrial Index suffered a combined fall of over 8% [7]. A stockmarket sell-off in response to an act of terror is no surprise. However, it was not simply the attack on democracy that caused investors’ concern. It was the anticipation of McKinley’s successor, Vice President Theodore Roosevelt, and the threat he posed to the status quo of corporate America.

If Roosevelt’s foreign policy was guided by speaking softly and carrying a big stick, the same might be said for his approach to the trusts.

In his opening speech to Congress, Teddy Roosevelt laid out his tough, but considered strategy. Claiming most Americans thought trusts “Hurtful to the general welfare”, he vowed “to rid the business world of crimes of cunning.” Yet he tempered this message, saying “combination and concentration” should not be prohibited but controlled “within reasonable limits” and he had no “lack of pride in the great industrial achievements” of America’s big businesses [8].

As labour conditions and inequality continued to worsen, the public bayed for monopolists’ blood.

SHOTS FIRED

The president came to office with a vigour rarely seen before, or since. Wall Street was wary of his proclivity for regulation. According to his biographer, HW Brands, few things were too minor for him to try to regulate. He changed the rules of American football, introduced martial arts classes at the Naval Academy and even changed the design of soon-to-be-minted coins [9].

It didn’t take Roosevelt long to turn his attention to the trusts. His weapon of choice was the 1890 Sherman Antitrust Act – existing legislation that had gathered dust on his predecessors’ shelves. The Sherman Act was a “comprehensive charter of economic liberty aimed at preserving free and unfettered competition as the rule of trade [10].” It made it a felony to “monopolize any part of the trade or commerce among the several states [11].”

In 1902, Roosevelt filed a suit against the largest railroad trust in the country, JP Morgan’s Northern Securities Company [12]. The lawsuit was successful, and the Supreme Court indicted the trust for “depriving the public of the advantages that flow from free competition.” The court ordered the break- up of the conglomerate into independent competitive railroads. The trust was busted, and a precedent was set.

As labour conditions and inequality continued to worsen, the public bayed for monopolists’ blood. Roosevelt was attuned to public sentiment, and his election to a second term in 1904 was the ultimate endorsement of his trustbusting agenda. He continued apace, filing suits against 43 major corporations throughout his presidency [13].

MONOPOLIES AND THE MARKET

In 1907, the Dow Jones crashed, falling 38.1% from peak to trough [14]. The collapse owed, at least in part, to Roosevelt’s continued investigation of John D Rockefeller’s Standard Oil Company. Journalist Ida Tarbell had exposed the malpractices of Standard Oil [15], and an Interstate Commerce Commission report confirmed the use of illegal methods to gain advantage over its competitors [16]

Investors panicked, blaming the president’s antitrust policy. For some, Standard Oil had lubricated the engine of growth in the US economy. Prosperity relied on this monopoly and the low prices that came with it.

Roosevelt remained typically steadfast. He decried his accusers and pointed the finger at “Certain malefactors of great wealth” who had provoked the panic to “discredit the policy of the government”. The market collapse was caused not by his regulation of the trusts, but by “the speculative folly and the flagrant dishonesty of a few great men of wealth [17].”

Source: Federal Reserve of St Louis, US dollars per share, monthly, not seasonally adjusted

The Standard Oil case was one of several events that appear to have moved markets – illustrated in the chart above. Though it was not as simple as logic might suggest: more regulation equals stocks down, failed regulation equals stocks up. At times, the market was receptive to Roosevelt’s antitrust rhetoric. Throughout his presidency he was creative, diplomatic and selective in dismantling monopoly power.

BIGGER, BETTER, BUSTER

Roosevelt is cheered for his role in breaking up the monopolies. It would be quite wrong, however, to see him as anti-big business or, indeed, markets. Rather, he acknowledged that “these big aggregations are an inevitable development of modern industrialism” but drew the line “against misconduct, not against wealth [18].” His trustbusting was pragmatic, based on the merits of individual cases, not ideology.

Matt Stoller, author of Goliath: The 100-Year War Between Monopoly Power and Democracy, points to Standard Oil as a case in point [19]. The business was extraordinarily profitable, but it had misallocated capital and centralised the oil industry inefficiently.

In 1911, the Supreme Court broke the trust up into 34 separate companies, which were forced to compete. This cohort included entities from which some of today’s market leaders, Chevron and Exxon for example, trace their roots. Shareholders did exceptionally well – and Rockefeller’s personal fortune quintupled.

Our tendency as investors is to seek out the innovators, the eventual market dominators. When we consider the US’s leading companies today – Meta (formerly known as Facebook), Amazon, Alphabet, Tesla – perhaps we should question whether their insatiable appetite for acquisition and growth is still producing the greatest innovation or shareholder value.

WE THE PEOPLE

Antitrust has been only a minor part of US government policy for most of the past 40 years. That is changing. Lina Khan has launched an antitrust renaissance and now heads one of Washington’s two primary antitrust enforcement arms, The Federal Trade Commission. Khan shares Roosevelt’s intellectual rigour, hardiness and determination.

In 2017, her paper Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox argued that the current framework in antitrust – specifically its pegging of competition to ‘consumer welfare’, defined as short-term price effects – is unequipped to capture the architecture of market power in the modern economy [20].

Khan’s vision for antitrust represents a shift in how Washington governs corporate America.

If there is a lesson from early twentieth century trustbusting, perhaps it is this: for antitrust regulation to be enforced, the public must wish it. Roosevelt was galvanised by voters’ sentiment – a shared outrage against unfairness and exploitation. This feeling emerged despite the cheaper goods and the perception of progress imparted by the trusts.

Can we look past Amazon’s unbeatable prices, or find new ways to communicate outside the ‘Metaverse’?

If the answers to these questions change, investors should brace for a new wave of trustbusting and all the attendant challenges – and opportunities.

[1] Brandeis (1934), The Curse of Bigness

[2] Klobuchar (2021), Antitrust: Taking on Monopoly Power from the Gilded Age to the Digital Age

[3] DiLorenzo (1985), The Origins of Antitrust: An Interest-Group Perspective

[4] Ferguson (2021), Blind to History, Facebook is in the Trustbusters' Crosshairs

[5] Constitutional Rights Foundation (2007), Progressives and the Era of Trustbusting

[6] Baker, Frydman and Hilt (2018), Political Discretion and Antitrust Policy: Evidence from the Assassination of President McKinley

[7] Factset

[8] Roosevelt (1901), State of the Union Address

[9] Brands (1997), TR: The Last Romantic

[10] Federal Trade Commission

[11] NYU Stern School of Business

[12] Cornell Law School

[13] Bittlingmayer (1993), Tee Stock Market and Early Antitrust Enforcement

[14] Federal Reserve Bank of St Louis

[15] Tarbell (1904), The History of the Standard Oil Company

[16] US Library of Congress

[17] Bittlingmayer (1996), Antitrust and Business Activity: The First Quarter Century

[18] Roosevelt (1902), State of the Union Address

[19] Stoller (2019), Why US Businesses Want Trustbusting |

[20] Khan (2017), Amazon's Antitrust Paradox, Yale Law Journal

This article first appeared in The Ruffer Review 2022.

Past performance is not a guide to future performance. The value of investments and the income derived therefrom can decrease as well as increase and you may not get back the full amount originally invested. Ruffer performance is shown after deduction of all fees and management charges, and on the basis of income being reinvested. The value of overseas investments will be influenced by the rate of exchange.

The views expressed in this article are not intended as an offer or solicitation for the purchase or sale of any investment or financial instrument, including interests in any of Ruffer’s funds. The information contained in the article is fact based and does not constitute investment research, investment advice or a personal recommendation, and should not be used as the basis for any investment decision. References to specific securities are included for the purposes of illustration only and should not be construed as a recommendation to buy or sell these securities. This document does not take account of any potential investor’s investment objectives, particular needs or financial situation. This document reflects Ruffer’s opinions at the date of publication only, the opinions are subject to change without notice and Ruffer shall bear no responsibility for the opinions offered. Read the full disclaimer.