The decision to sell or not to sell the family business: Do emotions matter?

Anheuser-Busch, Champagne Taittinger, Malt-O-Meal and The Wall Street Journal are some illustrative examples of the behaviour of family owners relinquishing the control of the business, not without expressing regret after the sale.

In family businesses, the underlying processes of the divestment decision-making are not only driven by financial logics, but also by emotional logics. How do they play out across family business archetypes and what families can do to make the right decision of selling or not selling the business with limited regret?

Combining financial and emotional considerations

Traditionally, business owners choose to sell their shares when the opportunity meets their expectations in terms of financial value (FV) creation. In family businesses, the interaction of family, business and ownership systems introduces another dimension to such a decision. Family owners include, in fact, the emotional value (EV) creation in their reasoning, albeit to different extents.

While the financial value reflects the net present value of the future cash-flows of the business, the emotional value stands as the net present value of the emotional cash-flows, that is the difference between the positive and the negative emotional cash flows, discounted at the expected emotional rate of return of the owners (Labaki & Hirigoyen, 2020).

The positive emotional cash-flows include, among others, pride, family cohesion and community recognition while the negative emotional cash-flows include family tensions, rivalry and conflict (Astrachan & Jaskiewicz, 2008). The minimum price (V) at which a family owner would be willing to sell an endowed entity includes both his or her perceived financial and emotional value of that entity (Zellweger & Astrachan, 2008), as follows: Total Value (V) = Financial Value (FV) + Emotional Value (EV).

Family owners do not always have similar expectations regarding the components of the value creation equation. Therefore, divergent perceptions among the owners might lead to different decisions relative to the sale and to different reactions following the sale.

Understanding the dual expectations of family members

Understanding the dual expectations of family members

It is not uncommon for some family owners to acknowledge a negative emotional impact of the sale of the family business, sometimes despite a positive financial impact. For John Brooks from Malt-O-Meal, the family business sale was not satisfying neither at the personal level nor at the family level, as it left a void in his life and set the three branches of the family apart. Christopher Bancroft, former family owner of The Wall Street Journal, also expressed regret at selling the family business: “We wouldn't have sold if we had known”.

When the senior generation decides to sell out, it often becomes very hard for the next generation members to reverse that decision, despite its emotional attachment to the family business, as shown by August IV from Anheuser-Busch. Sometimes the next generation can succeed in buying back the business after its sale, as initiated by Pierre-Emmanuel Taittinger (pictured left) from Champagne Taittinger, restoring the control in the family’s hands.

For the divestment decision to lead to emotional value and financial value creation in line with the expectations, my recent co-authored research suggests adopting a holistic perspective on the process, starting by the identification of the emotional archetype of the family business.

Navigating the divestment decision in different emotional archetypes

The anticipation and management of the emotional dynamics in regards with the divestment decision requires understanding the emotional archetype of the family business, that is the way emotions bind the business and the family.

Not all family businesses represent a homogeneous form of organisation. According to Labaki et al. (2013), a family business can stand as one of three main emotional archetypes and evolve from one to another across the life cycle: Enmeshed, Balanced and Disengaged. Enmeshed and Balanced emotional archetypes of family businesses tend to characterise first and second-generation businesses whereas Disengaged ones tend to characterise the third and subsequent generations.

In Balanced Family Businesses (BFB), family owners are generally highly identified with the business and have moderate to low levels of conflicts of interests in regards with the future outlook of ownership. They manage to skillfully balance the weight of financial value and emotional value expectations. Their preferences can be two-fold. On the one hand, they seek to maintain the family control of the business in line with the expectations.

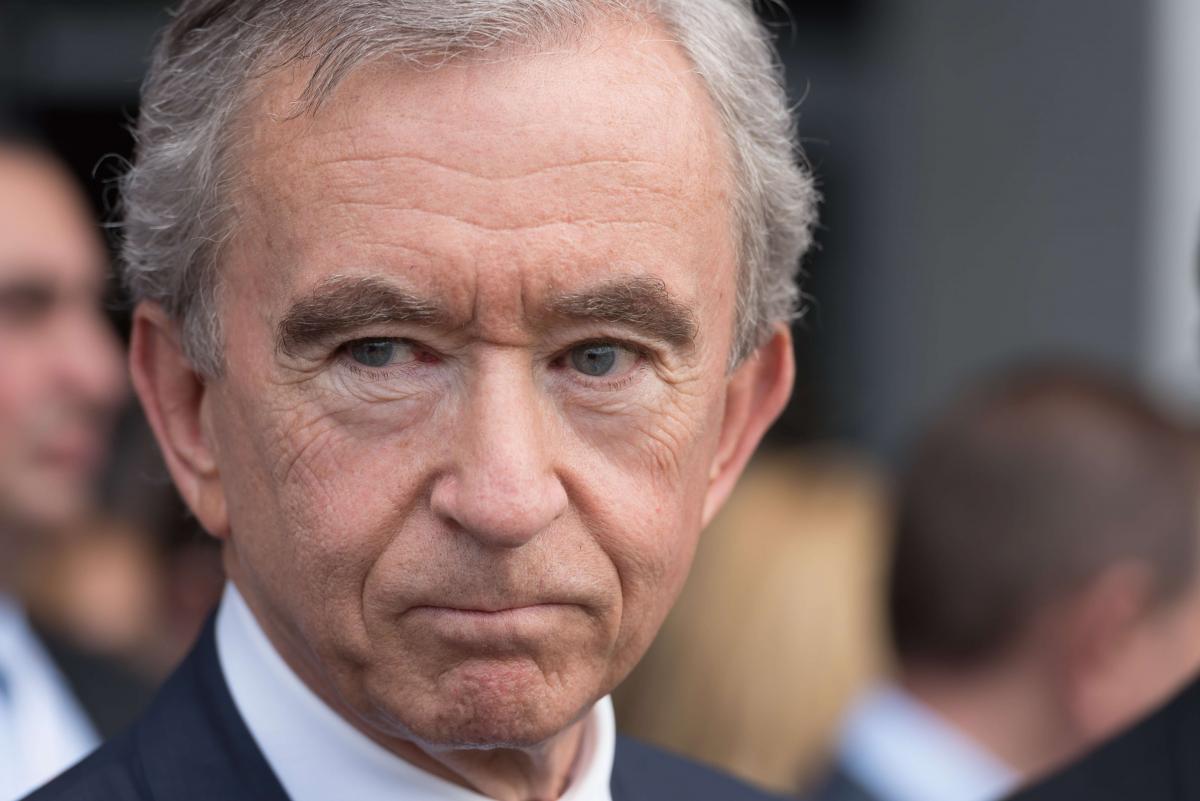

This was the case for Hermès where the family owners stayed united and consolidated their commitment to a long-lasting ownership despite threatening attempts from an outside shareholder, LVMH, led by family business principal Bernard Arnault (pictured above), significantly increasing its stake in the capital. On the other hand, they seek to sell the business in acceptable conditions that minimise the owners’ regret after the sale. This is the case when the core business is the object of family tensions that could be resolved because of the sale and/or when the proceeds of the sale could be invested in new projects in line with the family’s latest interests, thus re-uniting the family or at least a group of family owners together, as illustrated by Lacoste.

In Enmeshed Family Businesses (EFB), family owners have extremely high levels of identification with the business and are less likely to accept an arbitrage between financial and emotional value. They tend to be aligned in terms of expectations with almost inexistent conflicts of interests. The emotional value the family members derive from their ownership is often regarded as predominantly important. This often leads the family not to sell the business, even when it is going through a difficult financial situation, as the regret post-sale is regarded as extremely high by the family owners.

In Disengaged Family Businesses (DEF), most of the owners are likely passive, weakly identified with the business which they predominantly view from a financial standpoint. They hardly accept a decrease in their expectations of financial value for the benefit of emotional value. Conflicting interests tend to exist among the majority or passive owners who are disengaged and the minority or active family owners who still have a sense of identification to the family business. The decision to sell or not to sell is therefore made differently across owners and might lead to different emotional reactions and types of arbitrages between the financial value and the emotional value.

In Disengaged Family Businesses (DEF), most of the owners are likely passive, weakly identified with the business which they predominantly view from a financial standpoint. They hardly accept a decrease in their expectations of financial value for the benefit of emotional value. Conflicting interests tend to exist among the majority or passive owners who are disengaged and the minority or active family owners who still have a sense of identification to the family business. The decision to sell or not to sell is therefore made differently across owners and might lead to different emotional reactions and types of arbitrages between the financial value and the emotional value.

Château d’Yquem offers an illustration of divergent interests among owners, 40 of whom sold their shares following a financial proposal that met their financial value expectations whereas one of the owners, Count Alexandre de Lur Saluces (pictured right), refused to sell his 8% of the capital partly because of missing considerations for the emotional value in the proposal. After a tough negotiation process and court battles, he agreed to sell his shares within revised conditions that met his expectations, including a higher financial value and a higher emotional value echoed by promises from the buyer to respect the tradition and values of the family business following the sale.

Towards exploring divestments as real options

Enmeshed, Balanced and Disengaged Family Businesses favour different divestment decisions with different combinations of emotional and financial value expectations. Additionally, the expected or experienced regret of family owners may lead them to sell or not to sell their shares and to do so in different terms (Hirigoyen & Labaki, 2012). While the identification of the emotional archetype is a first step towards anticipating the behaviour of family owners and managing the decision-making process, recent research recommends to go one step further by viewing divestment as a real option and outlining a series of possible scenarios that can turn into reality when the opportunity strikes (For further reading: Labaki & Hirigoyen, 2020).

To conclude, divestment remains one of the most important financial decisions of any business. In the family business, it certainly benefits from a thoughtful decision-making process embracing emotional dimensions as its consequences can be irreversible and regrettable, spreading beyond the business itself and impacting the family and the communities around.

References:

- Astrachan, J. H., & Jaskiewicz, P. (2008). Emotional Returns and Emotional Costs in Privately Held Family Businesses: Advancing Traditional Business Valuation. Family Business Review, 21(2), 139-149

- Hirigoyen, G., & Labaki, R. (2012). The role of regret in the owner-manager decision-making in the family business: A conceptual approach. Journal of Family Business Strategy, 3(2), 118-126.

- Labaki, R., Michael-Tsabari, N., & Zachary, R. K. (2013). Exploring the Emotional Nexus in Cogent Family Business Archetypes. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 3(3), 301–330.

- Labaki, R., & Hirigoyen, G. (2020). The Strategic Divestment Decision in the Family Business Through the Real Options and Emotional Lenses. In Palma-Ruiz, Barros, & Gnan (Eds.), Handbook of Research on the Strategic Management of Family Businesses (pp. 244-279): IGI Global.

- Zellweger, T., & Astrachan, J. (2008). On the Emotional Value of Owning a Firm. Family Business Review, 21(4), 347 - 363.