A capital idea: Funding the family enterprise

In 2010 an enterprising British luxury chocolate chain, co-founded by Angus Thirlwell - a second-generation member of the Mr Whippy ice cream business, issued the first-ever 'chocolate bond'. Hotel Chocolat raised £4.2 million ($6.3 million) from the mini-bond. Its returns included receiving a box of chocolates every two months. Last year it launched its second 'chocolate bond', offering annual returns of 7.25% in the form of in-store credit, or a monthly box of chocolates. It aimed to raise a further £10 million to fund the growth of its portfolio of cocoa bar-cafés, chocolate boutiques and flagship sites, among other developments.

Other family businesses have been getting in on the act. Earlier this year family-owned Scottish craft beer brewer Innis & Gunn joined the trend, launching £3 million in mini-bonds to build a brewery. Their “BeerBond” aims to pay 7.25% interest each year, with investors' initial investment returned on maturity after four years. Bondholders will also receive a 12.5% discount on online beer purchases.

These so-called mini-bonds can be appealing to smaller, often early-stage businesses that are looking to raise a few million dollars without giving away equity or lending from mainstream institutions. Most of these bonds are small, however in 2011, British retailer John Lewis managed to raise £58 million in this manner.

This British innovation is relatively new. Will King, founder of King of Shaves, claims he invented the idea. In 2009 he issued his “Shaving Bond”, which yielded “12 times the present bank rate” – 6% interest over three years plus a free product. He managed to raise over £5 million to fund the firm's growth.

“Banks ain't lending much dough these days. And this is hurting small-medium enterprises,” he said in 2011. “Back in June 2009 we debuted our innovative Shaving Bond. Many companies, including John Lewis, Caxton FX, Hotel Chocolat, Ecotricity have now followed – and this type of mini-bond finance raising, which connects customers with companies, as well as raising money is gaining credibility and momentum. This was our idea.”

Seven years on from the financial crisis family businesses remain wary of taking on too much debt. Yet with a persistent need to fund growth they are increasingly looking to non-bank channels to raise capital. Finding the right source of capital, however, can be difficult. A 2014 KPMG International survey showed that 58% of family businesses are currently seeking external financing to fund their investment plans, but unearthing the right strategic investment partner is challenging. A series of blighted initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2014, included the Rovati family, who pulled their listing of Italian pharmaceuticals firm Rottapharm, and the stalled listing of Saudi Arabia's Construction Products Holding, part of the family-controlled Binladen Group, underline the challenges of public listings. So what are the options for families that don't want to take on traditional debt or relinquish control by reducing their ownership stake? And what are the pitfalls of these options?

Seven years on from the financial crisis family businesses remain wary of taking on too much debt. Yet with a persistent need to fund growth they are increasingly looking to non-bank channels to raise capital. Finding the right source of capital, however, can be difficult. A 2014 KPMG International survey showed that 58% of family businesses are currently seeking external financing to fund their investment plans, but unearthing the right strategic investment partner is challenging. A series of blighted initial public offerings (IPOs) in 2014, included the Rovati family, who pulled their listing of Italian pharmaceuticals firm Rottapharm, and the stalled listing of Saudi Arabia's Construction Products Holding, part of the family-controlled Binladen Group, underline the challenges of public listings. So what are the options for families that don't want to take on traditional debt or relinquish control by reducing their ownership stake? And what are the pitfalls of these options?

Mini-bonds for mini adventures

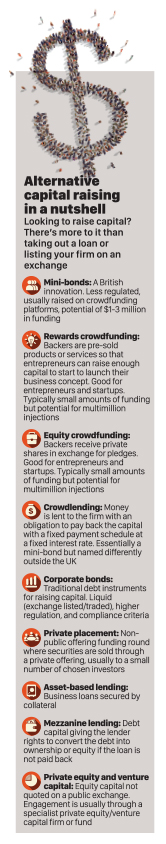

Mini-bonds are usually issued through crowdfunding platforms like the UK's Crowdcube. Like conventional bonds, mini-bonds usually have fixed maturities of around three to five years, with investors receiving interest twice annually.

The advantage for businesses wishing to raise capital can be seen as a disadvantage for investors; mini-bonds don't face the same regulatory listing requirements as conventional bonds, so they're easier to issue. But investors don't get the same comprehensive information – or protections – on their investment.

Because of their uniqueness as a fixed income investment, comparatively higher interest rates and fun added perks, such vehicles are increasingly appealing to smaller mainstream investors. But there's a growing crowd of investment professionals who are warning of the dangers of such instruments.

“A new source of finance for businesses at a time when bank lending conditions are difficult is something to be welcomed. What we would not want, however, is this to come at the expense of investor protections for bondholders,” says James Tomlins, a high-yield bond fund manager at London-based M&G. “These protections have evolved over several decades in the institutional bond market and serve an important function in protecting investor rights and indeed their capital. These protections really matter when things go wrong and we are yet to see any default in this particular market so this deficiency is yet to manifest itself.”

Mini-bonds are non-tradable, which means once bought direct from the issuer, there is no secondary market. For investors this means their cash is locked in to the vehicle for the duration, with no ability to sell out. For issuers, this arguably means they maintain more control and aren't victim to sudden price moves.

In February, UK watchdog the Financial Conduct Authority, reviewed that country's crowdfunding market and released a warning to investors: “It is important for prospective investors to understand the risks. Mini-bonds are illiquid and can be high risk, as the failure rate of small businesses is high.”

Yet so far such a warning has not seemed to dent the popularity of either issuers or investors and so far there have been no serious defaults of mini-bonds.

Keeping control

For larger family enterprises, mini-bonds might not provide enough capital-raising potential for their strategic plans. In such cases, unsecured debt is becoming increasingly preferential over giving up equity.

In August, Italian family firm Illy Caffè chose to issue senior unsecured debt of €70 million for business expansion, rather than release equity. The loan is not rated and is fully underwritten by Pricoa Capital Group. The notes have a 12-year maturity with a 10-year average life and an annual fixed coupon of 3.35%.

In August, Italian family firm Illy Caffè chose to issue senior unsecured debt of €70 million for business expansion, rather than release equity. The loan is not rated and is fully underwritten by Pricoa Capital Group. The notes have a 12-year maturity with a 10-year average life and an annual fixed coupon of 3.35%.

“This bond issue is an important sign of confidence in financial markets. It also proves our project's reliability at a time when Illy Caffè is rolling out a global development plan,” says Illy Caffè chairman and CEO Andrea Illy.

Speaking exclusively with CampdenFB, when asked what was the reasoning behind choosing to raise a bond instead of using other capital raising methods, Andrea Illy says: “It was our choice to rebalance the debt mix, raising a bond with very interesting financial ratios and competitive conditions. It is similar in many ways to a bank loan but outside of the banking system and in terms of duration and amortisation, certainly much better than bank loans. Any other method (venture capital, private equity) would entail an agreement about the equity itself.”

Like many family firm leaders, Illy is keenly aware of market forces but adamant about retaining control over a business that has been grown over many generations. In fact he sees family ownership as a positive in such economic conditions.

“If I take Illy Caffè as an example, throughout the recent period of financial turmoil – since 2007 – the sustainability of our business model did not alter our capability of raising new capital,” says Illy. “In fact, we raised our first bond ($66 million) in 2012, at the peak of the Italian economic crisis. I would therefore say that the sustainability of family businesses is the key to keep this general ability up.”

While many commentators believe that it is more difficult for family businesses to raise capital privately now, compared to the past or compared to public markets, Illy firmly disagrees.

“I don't think it is more difficult compared to the past nor to other types of firms: but, again, the key is the sustainability of the business model,” he says.

In that vein, Illy gives the following advice to other family business leaders who wish to grow their business while ensuring control and direction of their own company: Never compromise nor give up on your own values, heritage, capacity for innovation, or your long-term vision.

And it is fair advice from a family member that has helped lead his firm through interesting times. Anna, the widow of founder Ernesto is the matriarch and honorary chairman of Illy Caffè, while her children Francesco, Riccardo, Anna and Andrea run the firm. The $80 billion coffee industry is presently in an era of consolidation – historically dangerous times for many family-owned operations.

In July, Lavazza, Illy's larger Italian rival, made an €800 million offer for French competitor Carte Noire, and Illy Caffè has long been seen as a potential acquisition target by bigger players in the sector.

“We are a family business and we have two things to protect. One is the dream of the founder to offer the greatest coffee in the world and the other is our family name. This requires a long-term vision and cannot be achieved with quarterly results,” says Illy, whose consolidated revenues for Illy Caffè were almost €400 million last year, up 4.5% year-on-year. Illy plans to double revenues in the next ten years, opening 600 sales points worldwide.

A further long-term goal of Illy is to make the firm eligible to join the Henokiens Association, a prestigious association of firms owned by the same family for more than 200 years.

In the US, where mini-bonds are yet to gain a foothold, crowdfunding has been the source of capital raising for mostly startup entrepreneurial ventures rather than established family businesses. However, the potential funds to be raised are comparable to smaller corporate bond issuances. So far the record for the highest crowdfunding campaign was $88.3 million raised by a video game developer, Chris Roberts, with over 972,000 backers.

New kid on the block

Crowdfunding, as opposed to mini-bonds or crowdlending, comes in two main flavours: so-called rewards crowdfunding, where backers are pre-sold products or services so that entrepreneurs can raise enough capital to start to launch their business concept; or equity crowdfunding, where backers receive private shares in exchange for pledges.

Crowdfunding, as opposed to mini-bonds or crowdlending, comes in two main flavours: so-called rewards crowdfunding, where backers are pre-sold products or services so that entrepreneurs can raise enough capital to start to launch their business concept; or equity crowdfunding, where backers receive private shares in exchange for pledges.

The growth of these vehicles was borne as a reaction to the credit crunch of the last decade. After the financial crisis, the US government sought to make it easier for SMEs to raise capital, and the 2012 Jumpstart Our Business Startups “JOBS” Act seeks to make it easier for firms to go public or raise capital privately via methods such as equity crowdfunding.

Similarly in early September, the European Union financial services commissioner, Jonathan Hill, said firms needed to be weaned off their reliance on traditional bank lending, urging them to better utilise crowdfunding and venture capital.

“If you've got a system that's very dependent on one source of funding, and you have a contraction in bank funding like we had, then that has a very real knock on to the economy,” Hill told CNBC during the Ambrosetti economic forum in Italy. “If we can diversify and spread it, we can also help achieve a greater degree of financial stability.”

But even though there have been one or two large, multimillion-dollar fund raisings, the average successful crowdfunding campaign is only around $5,000, according to Forbes. It's a case of the geekier (video games), sexier (movie projects), or quirkier the idea, the more likely it is to perform well; a crowdfunding project to make a Veronica Mars movie based on the popular TV show met its funding goal in 10 hours and ultimately raised $5.7 million, while a campaign to launch a card game featuring exploding kittens garnered $8.8 million in backing.

While crowdfunding might not be a suitable capital-raising tool for large family businesses, smaller firms or entrepreneurial ventures could well benefit from a crowdfunding strategy.

Private placements

A more structured option for raising capital could be private placement. This is a non-public offering funding round where securities are sold through a private offering, usually to a small number of chosen investors. Private placements let you keep control of your company. Rather than offer shares to the public, the firm remains private. The regulatory requirements are less burdensome, and the cost and time needed to raise capital is reduced.

Platforms exist where businesses looking to raise capital can be matched up with serious investors. Peter Williams founded ACE Portal in 2010 to make it easier for businesses to sell securities privately. Previously, companies looking to raise capital via a private placement would need to find the right broker who had broad connections to the right investors, handling fund sourcing through personal networks or over the phone or via email.

“From a process perspective, that's inefficient and from an investor perspective it's ridiculous,” says Williams.

The ACE portal, now owned by NYSE Euronext, lets broker-dealers post and manage private placements offers, while family offices and ultra-high net worth investors can search for offerings by their own criteria.

The portal is specifically for private firms to raise capital, says Williams; ACE doesn't trade existing shares in privately-held companies. Similarly, as opposed to crowdfunding platforms which are popular with startups, ACE's client base is established firms wanting to raise at least $5 million – with an average deal size around $50 million.

Family office co-investments or funding from like-minded private investors or other family business owners are also viable ways to raise funds for your business without needing to use investment banks or public offerings – although they are often seeking equity stakes.

The Global Family Office Report 2015 found almost 14% of the average family office portfolio is allocated to direct private equity – equivalent to $108 million each office. To gain wider exposure to such opportunities they often join formal or informal deal clubs. In the US, the Campden Wealth*-owned Institute for Private Investors operates a regular deal collaborative where its private investor members share deals and opportunities amongst each other. Outside the US, Campden Wealth operates a peer-networking membership club for family offices to present and review direct investment pipelines.

More traditional means

Other more traditional ways to raise capital include asset-based lending (business loans secured by collateral), mezzanine lending (debt capital giving the lender rights to convert the debt into ownership or equity if the loan is not paid back), and, of course, private equity and venture capital.

After a sharp drop in activity during the global financial crisis, private equity and venture capital has since seen somewhat of a renaissance. According to the Washington-based industry lobbyist group, the Private Equity Growth Capital Council, by Q2 2009 private equity capital invested had slumped to just $30 billion from a peak of $300 billion in Q4 2007. In Q2 2015 that figure had increased to $112 billion for the quarter.

While private equity can be a valuable source of capital for family business owners, matriarchs and patriarchs should know what they are getting themselves into.

“As an owner, you have to ask yourself: What does it mean to partner with a private equity firm? What do I gain? What do I give up?” Stuart Sorenson, a partner at law firm Duane Morris in San Diego says, explaining that private equity houses look for businesses “that could benefit not only from a capital infusion but also from the operational and managerial expertise that they are able to provide to their portfolio companies.”

Benefitting from “operational and managerial expertise” can often mean a more hands-on approach from the private equity house and family firms need to weigh the pros and cons of such a prospect.

Benefitting from “operational and managerial expertise” can often mean a more hands-on approach from the private equity house and family firms need to weigh the pros and cons of such a prospect.

“Partnering with a private equity firm may mean giving up a controlling interest, possibly economic and voting, in your company,” says Sorenson. “But it may mean gaining a partner that can not only provide professional oversight but also share the expenses and the risks of growing your business – a risk many business owners tend to underestimate.”

The ultimate questions for family businesses wishing to raise capital are: how much capital do I need, how much control am I willing to relinquish (if any), and does the family agree? In August, family members from Spanish retail empire El Corte Inglés went public with concerns about a €1 billion financing deal. The privately-owned family business was handing over a 10% stake to Qatar's former prime minister. The rebel shareholders, Ceslar - an investment vehicle controlled by the founder's nieces, were later ejected from the board of directors.

Once these questions have been seriously considered, there are plenty of options open to family firms that don't involve walking into an investment bank or filing for a public offering.