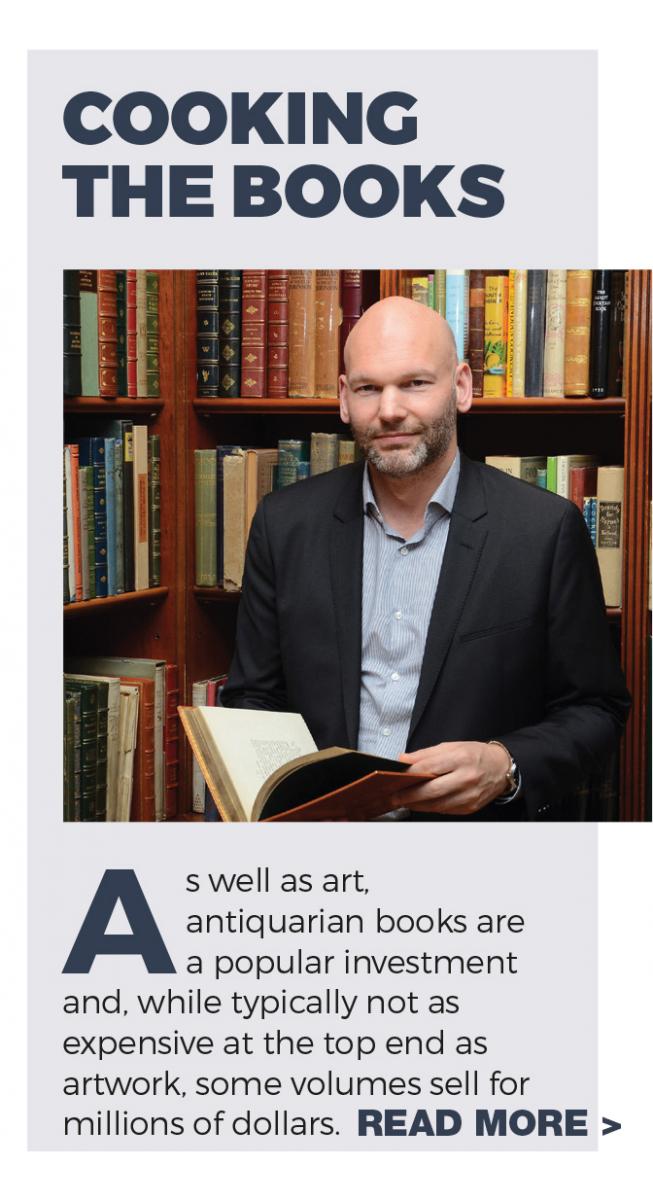

As pretty as a picture' Smart investments in the art world

With concerns over fraud and ownership, the art world offers myriad pitfalls for the unwary, causing experts to advise bringing in specialists to help ensure that investments do not turn sour. Daniel Bardsley reports

When the painting Judith Beheading Holofernes was presented in public for the first time earlier this year, some hailed it as a lost masterpiece.

One expert, confident that the picture was by the Renaissance master Caravaggio, suggested it could be worth an eye-watering €120 million ($133 million). Not bad for a piece apparently discovered in a dusty attic.

Yet although the image, with its blood, and partially severed neck, is gruesome enough to be the work of the celebrated Italian artist, some were unconvinced. They dismissed it as a fake and suggested it was the work of a Flemish painter who liked to copy Caravaggio's work.

That its origins will probably never be determined with certainty highlights the complexities involved in determining provenance in a multi-billion dollar market that has attracted its fair share of fraudsters over the centuries. The global art market achieved total sales of $63.8 billion in 2015 – although there is no estimate of the size of fraudulent sales.

Today it is big business, with art crime described as the United Kingdom's most lucrative criminal sector, apart from the drugs trade. Jeremy Asher, an associate at British law firm Ashfords LLP, that has acted in a number of art fraud cases, says “the whole area is fraught with difficulty”.

“If you invest a lot of money in art, you have got to be so careful,” he says.

“You have to use trusted sources, [but] even the top auction houses get it wrong. Many of the difficulties are to do with scientific analysis that shows the art work just does not stack up evidentially.

“You have to use trusted sources, [but] even the top auction houses get it wrong. Many of the difficulties are to do with scientific analysis that shows the art work just does not stack up evidentially.

“Or it could be that the art is OK, but the provenance is not. It's been made up after the event to make it look right.”

There is no shortage of cautionary tales.

The demise of the New York gallery M Knoedler & Co, operating since 1846, is among the most notorious. Before its 2011 closure, the gallery sold a string of works supposedly by such luminaries as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. Together raising more than $60 million, the paintings had been supplied by Glafira Rosales, an art dealer based in Long Island who had knowingly bought them from a New York-based Chinese forger, Pei-Shen Qian. Knoedler insisted it was unaware of the scam.

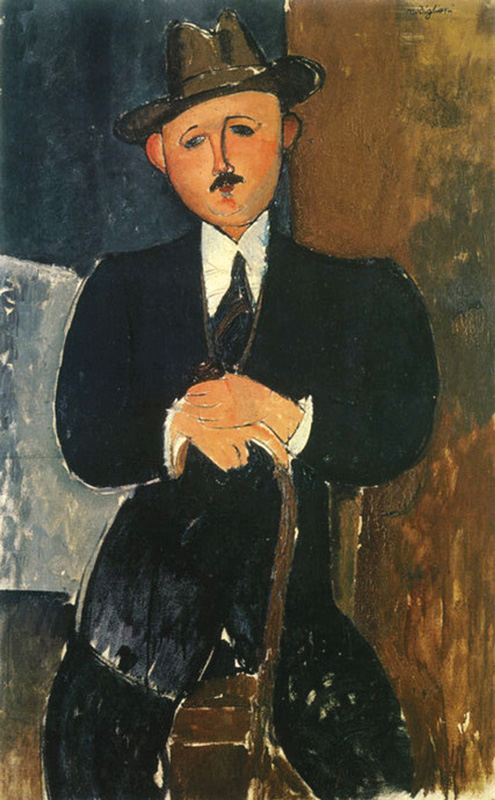

Other cases, often involving the Second World War, concern disputed ownership. A notable example centres on Seated Man With a Cane, a 1918 painting by Amedeo Modigliani, put up for auction in New York in 2008. No bids were made because of concerns over ownership: a Jewish gallery owner, Oscar Stettiner, was apparently forced to leave it behind when he fled Paris as the Nazis closed in. The painting was seized by the Swiss authorities in April 2016.

Other cases, often involving the Second World War, concern disputed ownership. A notable example centres on Seated Man With a Cane, a 1918 painting by Amedeo Modigliani, put up for auction in New York in 2008. No bids were made because of concerns over ownership: a Jewish gallery owner, Oscar Stettiner, was apparently forced to leave it behind when he fled Paris as the Nazis closed in. The painting was seized by the Swiss authorities in April 2016.

Art therefore presents risks that do not exist with other potential investments.

“If you look at our domestic markets, our equity markets, and bond markets are well regulated and offer clients a lot of protection and things can be done in a cost-efficient way,” says Adriaan Pask, chief investment officer of South African-based PSG Wealth.

“If you look at the art world, it isn't really a well-regulated area. The onus lies with clients to make sure they don't buy fraudulent pieces and they're insured and they're maintained. That's where the complexity comes into play.”

“If you look at the art world, it isn't really a well-regulated area. The onus lies with clients to make sure they don't buy fraudulent pieces and they're insured and they're maintained. That's where the complexity comes into play.”

To identify stolen work or those subject to Second World War provenance issues, databases such as London's Art Loss Register can be consulted. Buyers are advised to request search certificates from galleries or auction houses, or to order a search themselves at a cost of £60 ($79) + VAT, less for multiple searches.

Each year the register carries out about 400,000 searches of items on the market, although a clean result is not a guarantee: the database does not contain every art theft as not all are reported.

“No database is ever complete,” says Katya Hills, a client development manager at the register.

“We don't hold ourselves out to be the only source; people should ask about provenance from the person they're buying from,” she says.

“Ask for documentation and research the provenance to as far back to the date of creation of the work as possible.”

This can help to establish ownership history and details of previous sales, and buyers should also consult the catalogue raisonné, a detailed illustrated guide to the artist's work.

“It's mainly the Second World War-related cases that are more complex, because of the lack of documentation,” Hills says.

“It's been 70 to 80 years since the war, so documentation is limited. People may have to look into their family archives to demonstrate they owned a particular work.”

The Art Loss Register and other databases focus on ownership, and are less involved with authenticity, although the register does record fakes reported by police and artists' foundations. They pass on to clients information that a piece may be fake, but, unlike with items reported as stolen, do not request that possible fakes are withdrawn from sale.

Identifying forgeries is complicated by the fact that authentication committees, formed to verify an artist's work after his or her death, have in recent years often disbanded because of litigation or the threat of it. Andy Warhol's is among those to have closed.

To navigate the minefield, buyers sometimes engage art consultants who help select pieces. There have been rare cases where they have been dishonest – the German art specialist Helge Achenbach was handed a six-year jail term in 2015 for extracting inflated commissions from the late Aldi heir Berthold Albrecht – but typically their expertise, while not cheap, offers reassurance.

To navigate the minefield, buyers sometimes engage art consultants who help select pieces. There have been rare cases where they have been dishonest – the German art specialist Helge Achenbach was handed a six-year jail term in 2015 for extracting inflated commissions from the late Aldi heir Berthold Albrecht – but typically their expertise, while not cheap, offers reassurance.

Judith Selkowitz, president of New York-based Art Advisory Services, says experience is key.

“If they're going to go to an art adviser, they should go to one who has been in the business for at least 10 years and who has had a lot of experience. [The adviser] understands what quality art is and understands what they need to do to ensure that the artwork is real and in good condition,” she says.

For authentication, consultants may bring in an expert on that artist, something Selkowitz “has no problem doing” when necessary.

Specialists like Dr Nicholas Eastaugh, director of London's Art Analysis & Research, provide technical analysis of pictures to help with authentication. This can complement art history analysis.

“We're specialists in looking at the material structure in art – are the materials appropriate for the supposed date and authorship? We're testing the material structure of the painting to see what it is made of and putting that in some historical context,” he says.

Buyers who want such analysis may find their bill totalling thousands of dollars.

Given the complications, some suggest avoiding vintage works.

“I would always suggest, if you're going to invest in art and you really want to play safe, you should be investing in modern artists,” says Asher.

“You're going to have the security of knowing exactly where it came from and being able to prove it, and hopefully you will be onto the next big thing.”

Aside from authentication, buyers need an accurate valuation. Experts recommend checking auction records for the previous decade and researching an artist's current prices. A conservator may be brought in to check on condition, with experts saying buyers should not rely just on a gallery or auction house's in-house specialist.

Establishing an accurate value in advance is important so that buyers do not end up paying over the odds, especially as there is the risk of underhand auction tactics.

“There's a certain amount of duping that goes on within the bidding process; it can be very clever – people hiding behind pillars and staircases, bidders using a number of different agents with sellers bidding up the price,” says Asher.

Bidders can sometimes be their own worst enemies, getting carried away and ending up with “buyer's remorse” when they pay more than the piece is worth.

However, those who take the plunge should be able to keep the risks to a minimum – if they have done their homework.

“Anybody can make a mistake, but at least if you have taken the steps to consider the price, consider the conservation, consider what condition the painting is in, look at the provenance and do your research, at least you have a very good chance that it's totally fine,” says Selkowitz.