Sponsored feature: High-tech harmony

From designing and outfitting the interiors for a 150-metre superyacht to turnkey development of a 4,000 sq mhome in the Swiss Alps straight from the set of a James Bond film, technology is an essential cog that helps Deutsche Werkstätten Hellerau's (DWH) manage complex design projects for their private clients around the world.

Technical skill has always played an important part in helping the 115-year-old Dresden-based firm, but today this harmony between high technology and craftsmanship is even more important.

“Beforehand we would only have been given a smaller part of the project, the joinery or the cabinetry, now we are given complete projects,” says DWH's managing director Jan Jacobsen.

“If we are building or are responsible for a construction process in a private house which has 50 rooms or a superyacht, this will involve a lot of specialists and special tasks,” he adds.

“Our clients are extremely demanding. We have had to learn to manage the highly complex working processes which are necessary to fulfil our client's requirements. This is the key to ensure top quality, adequate pricing levels and keeping deadlines previously agreed,” notes Jacobsen.

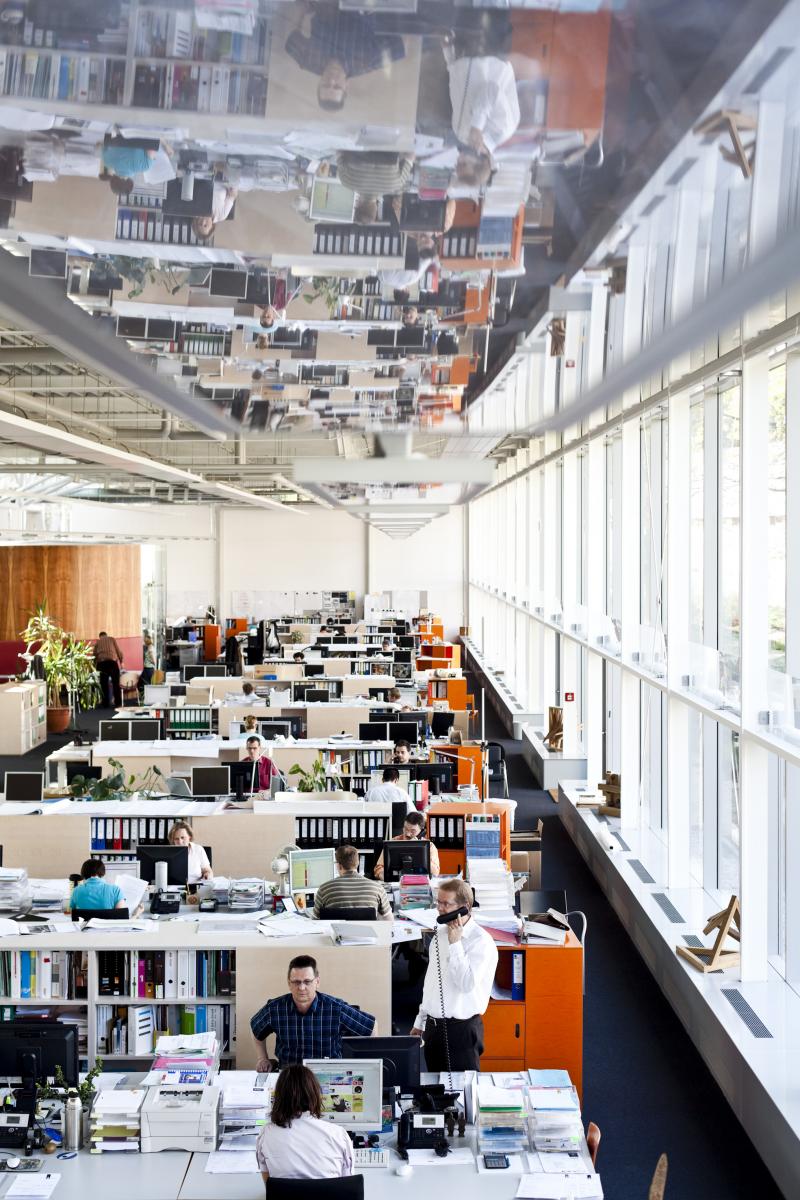

To manage this increasing demand for their engineering and management expertise, DWH uses technology in everything from 3D systems for its computer-based machinery to building information modelling software.

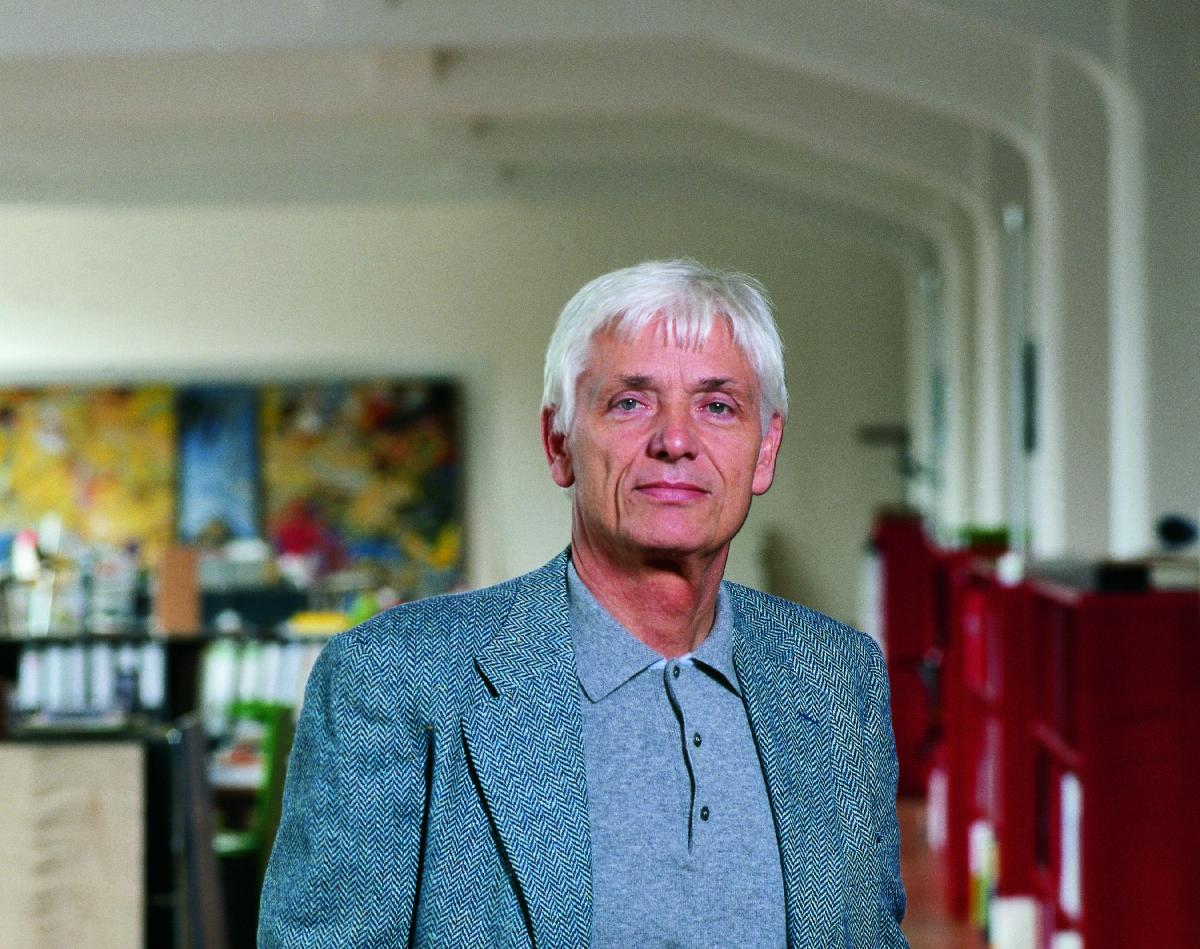

Fritz Straub is visibly proud of this spirit of excellence, innovation and craftmanship that suffuse everything that's created at the interiors and architectural firm. He is right to be, having resurrected DWH from near extinction in 1992 after persuading Treuhand, the agency entrusted with privatising East Germany's state-owned companies, to let him buy it.

Fritz Straub is visibly proud of this spirit of excellence, innovation and craftmanship that suffuse everything that's created at the interiors and architectural firm. He is right to be, having resurrected DWH from near extinction in 1992 after persuading Treuhand, the agency entrusted with privatising East Germany's state-owned companies, to let him buy it.

It's a spirit that spreads to his private clients, who although frequently very wealthy in their own right, want to be part of the building process when conceiving or constructing their superyacht or homes.

“Our clients love the process, they enjoy the mock-ups, they enjoy the material, they enjoy taking the decisions. Clearly it's a joy to them to craft and make something bespoke,” Straub adds.

These days, Straub and his 300-strong team, including managing director Jan Jacobsen, are involved in a rich array of projects. Their calling card is ingenious design solutions completed with top-end finishing by their master craftsmen with examples including a bespoke Gaudi-inspired library in the UK and outfitting a 180-metre 'megayacht' – the world's largest private motor yacht.

Yet this spirit of eye-popping innovation hasn't always been present. DWH's original founder, German Arts & Crafts movement pioneer Karl Schmidt, blended technology and craftsmanship into the DNA of the Dresden furniture company from its inception in 1898 until the Second World War. But following its nationalisation in 1946 as part of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) it was forced to discard making the top-quality furniture it had been synonymous for in pre-war Germany, and produce generic furniture for the next 40 years. Fast-forward 23 years and DWH is as far removed from its dark days in the GDR as it's possible to be – having exchanged its mass-market focus to design and build for private clients almost exclusively.

Today it's fused its 115-year-old heritage together with cutting-edge innovation to satisfy the demanding requirements of its international client. It typically handles five to 10 projects a year that can range in timescale from one to two years, and sometimes up to three. It has completed more than 25 commissions with one of the leading superyacht shipyards in Germany. The price tag for outfitting a 150-metre superyacht ranging from € 50 million to 70 million ($56 million to $78 million).

Today it's fused its 115-year-old heritage together with cutting-edge innovation to satisfy the demanding requirements of its international client. It typically handles five to 10 projects a year that can range in timescale from one to two years, and sometimes up to three. It has completed more than 25 commissions with one of the leading superyacht shipyards in Germany. The price tag for outfitting a 150-metre superyacht ranging from € 50 million to 70 million ($56 million to $78 million).

DWH has always been a client-led, rather than market-driven firm and in recent years; demand for its engineering and management capacity has grown.

One example was when a client travelled with his designer, wife and dog to inspect the mock-ups of his new yacht at DWH's headquarters in Dresden.

“He saw the company, he saw our open-plan office, he saw the production and the people and he turned to his project manager and says 'I could ask these guys to build a house in Switzerland', says Jacobsen. “Two months after this encounter here in our workshop with the client and his entourage, we signed a contract for a 4,000 sq mhouse in Switzerland.”

Throughout all of this, it would be tempting for Straub and Jacobsen to name-drop any one of their clients. But this is not something they would ever consider, even to a prospective customer.

“When we meet a new client, they often say 'Well you're nice people, it's a fantastic company, but I'd like to see one of your projects', says Straub. “The only thing we can say is, 'I'm very sorry, we have a non-disclosure agreement and you would not probably like that yourself if we did your house and then led strangers around your home.' Ultimately it's private.”

“When we meet a new client, they often say 'Well you're nice people, it's a fantastic company, but I'd like to see one of your projects', says Straub. “The only thing we can say is, 'I'm very sorry, we have a non-disclosure agreement and you would not probably like that yourself if we did your house and then led strangers around your home.' Ultimately it's private.”

Having demanding clients is not an issue with Straub or Jacobsen. “It's an advantage because they demand from us the most incredible things, which we have to develop. It's the basis for further innovation,” Straub concludes. “What was quality five years ago is not quality today.”