Panama Papers: Tax haven can wait

Will the Panama Papers mark a tipping point for families and their advisers? And what will families need to do to fend off public criticism? Paul Golden reports

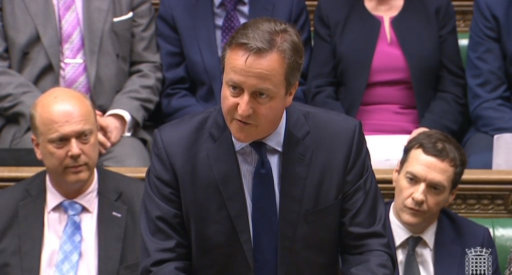

A mere two months before Brexit brought the curtain down on David Cameron's 11-year leadership of the UK Conservative Party, the former prime minister had only narrowly escaped an earlier end to his premiership.

The release of the Panama Papers in April had exposed his family's offshore tax arrangements to the full glare of public opinion. After several days of stalling and partial statements he finally admitted to benefitting from shares held in a Panama-based offshore trust set up by his late father.

The profit was pithy: £19,000 ($24,937), but the public backlash was profound. Cameron held onto his job by a slim margin, but it underlined the tenuous position wealthy families can find themselves in: eager for privacy, but wary of vilification in the public eye in an era when scrutiny of international tax structures is of public interest.

Public opinion can also influence corporate tax policy – family businesses take note. Last year Starbucks announced it was changing its approach to corporation tax in the UK despite also stating that it paid the level of taxes required by the law. The tax planning of other multinationals – most notably Google, Facebook, and Amazon - was also heavily criticised.

Holly Isdale, founder of Wealth Haven, says these companies have been quick to point out they are compliant with applicable tax laws and many of the structures used address concerns beyond taxes, such as privacy and security.

According to Isdale, many wealthy families choose to pay some level of tax to avoid having to change their lifestyles.

“The Panama Papers leak is a reminder to all families that there is no expectation of privacy and hence greater attention needs to be paid to security and communication issues,” she says.

“The hunt for legal private vehicles has taken on an increased importance.”

Sandy Loder, a fifth-generation member of the Fleming family and chief executive of AH Loder Advisers, reckons most wealthy families have stopped playing the tax evasion game, but adds they might still be playing the tax avoidance one.

“Families will use the most tax efficient option which is still legal,” he says.

“Obviously you will always have some who want to run close to the line or simply avoid paying tax, but it is getting much harder to do that. My concern is 'What are the consequences to the family in terms of reputation – both financially and personally.”

Loder believes those operating close to the line will be nervous.

“As for whether family advisers have to rethink their approach to managing the affairs of wealthy clients, it depends on the integrity of the client and the adviser.”

International tax expert Philip Marcovici has previously expressed concern about the lack of foresight and ethics in the wealth management industry. Marcovici warns that public reaction is fuelling an uncoordinated and dangerous move towards more disclosure requirements and complexity. He feels it is about time that wealth owners and the wealth management industry took a proactive role rather than defending the past.

“Planning will be more and more complex and expensive for families seeking to comply with an uncoordinated and developing system of disclosures and constantly changing rules,” he says. “Traditional offshore centres, in many cases, will not survive, but the growing role of midshore means that structures used will be even more complex than in the past.”

Marcovici believes it is time for advisers to truly align their interests with those of their clients and the communities in which they live.

“Income and wealth inequality, tax evasion, corruption, the human right to privacy and many other issues need urgent and sensible attention. Good advisers will be looking to not only react to the current situation, but to anticipate what is to come.”

One global independent family adviser delivered a stark assessment of how many wealthy families would have reacted to the Mossack Fonseca controversy, suggesting it was less of a wake-up call and more of an 'Are we going to be caught?' moment.

“The vast majority of wealthy families engage in complex financial structuring to minimise their tax bill, although much of that money is hidden within Delaware corporations rather than in far-away offshore locations,” he notes.

“The US is still a leading destination for money laundering with its ease of setting up LLC structures and because money laundering rules are particularly lax as they apply to US real estate.”

The point at which tax avoidance becomes tax evasion has become clearer in the post-Foreign Account Tax Compliance Act (FATCA) world and as the Common Reporting Standard (CRS) spreads.

The adviser, who wants to remain anonymous, stresses that paying as little tax as possible remains part of the DNA of just about every wealthy family.

“I would suggest that at least half of the world's wealthiest families are using structures that would struggle to stand up to a full and comprehensive audit,” he says.

“On the one hand they feel under attack from governments in austerity mode that are focusing on getting more tax revenue from the wealthy. On the other hand, there is sense that their tax burden is always too high no matter what it is.”

The use of offshore jurisdictions is just the latest example of wealthy families attempting to stay one step ahead of the tax authorities, he continues.

“They would have been shocked by the Panama Papers revelation as it came about from the theft of data rather than from a targeted campaign by diligent tax authorities. The lesson for wealthy families who have not cleaned up their tax structuring is that they live in perpetual and increasing risk of being discovered.

“There is no way of safely hiding assets from the taxman. Increasingly, discovery is coming from theft of personal data that is then turned over or sold to tax authorities. But any family that takes advantage of an amnesty needs to make sure it is squeaky clean because coming 'partially clean' will only place them on the radar of the tax authorities from that point onwards.”

When asked whether advisers are rethinking their approach to managing the affairs of wealthy families, he suggests that some will continue to recommend overly complex and questionable tax structures.

“Those advisers with good governance and sound ethics will recommend efficient and sound strategies,” he says.

“However, many advisers who see the possibility to earn easy and attractive fees by over-zealously minimising their clients' tax bills will continue to push the line between tax avoidance and tax evasion.

“Then there are those who deliberately arrange sham structures at the request of their international clients, knowing that there are still lucrative fees to be earned in doing so.”

Terence Pay, group head of tax at advisory firm Verfides, says wealthy families and their businesses are not moving away from the use of offshore financial centres and complex tax structures, where they are well advised and where those structures are appropriate.

“Offshore does not have to equate to tax evasion and this is a fact which was missed in much of the media hype surrounding the Panama Papers,” he observes.

“Offshore does not have to equate to tax evasion and this is a fact which was missed in much of the media hype surrounding the Panama Papers,” he observes.

“The use of offshore trusts and companies is permitted by many tax regimes. For instance, under UK tax law, UK tax residents who are non-domiciled can legitimately use such structures to shelter personal and business income from UK tax, providing certain conditions are met.”

However, Pay accepts that good advisers will steer away from artificial schemes and plan only on the basis of the spirit of local tax laws and underlying commercial realities. He also reiterates the point made by Isdale that offshore jurisdictions and structures provide many non-tax benefits for wealthy families and their businesses, such as confidentiality and asset protection. He suggests that these considerations are often more important than tax mitigation.

Good advisers will keep track of local legislative changes, as well as global initiatives such as the OECD/G20 base erosion and profit shifting project (BEPS), FATCA and the CRS, he adds.

“We have entered the era of global automatic information exchange,” concludes Pay. “There is no place for non-compliant or poorly advised structuring in the face of global transparency. Advice has to be sophisticated and tailor-made and there must be substance.

“Good advisers will already have been doing this, but I suspect we will see a welcome contraction in the market of offshore services sold purely on the basis of perceived 'secrecy' rather than forming part of well-formulated advice.”

According to the Financial Transparency Coalition, a global network of civil society, governments, and experts that promotes transparency in the global financial system, the Panama Papers revelations have shown the public how offshore financial structures are only available to a small group of the wealthy and powerful who use them to play by a different set of rules.

Liz Confalone is policy counsel at Global Financial Integrity, a non-profit organisation that conducts research into the impact of tax evasion. She suggests that if public reaction to the Panama Papers does not represent a watershed moment in attitudes to tax avoidance, it is hard to imagine what it would take to effect change.

Tax Justice Network senior analyst, Markus Meinzer, refers to geographical behavioural differences.

“Whilst European and US ultra-high net worth individuals may become more sensitive to reputational risks related to tax, I doubt that the same holds true for those from emerging economies and developing countries.

“However, there is some indication that advisers increasingly part ways on this question and that advising responsible and ethical tax behaviour is becoming more widespread.”

Confalone says if she were advising clients, she would be concerned about potential legal changes in many jurisdictions. She would also be thinking carefully about the reputational risks involved in using anonymous companies and other opaque corporate structures in their affairs.

“The fact that the formation of anonymous companies is legal in many jurisdictions did nothing to quell the public scorn directed toward many of the individuals named in the Panama Papers,” she concludes.

“It is now hard to ignore the disparity between what is, for the moment, technically legal and what is socially acceptable.”