Lay of the land: the conservation philanthropists saving ecosystems across the globe

This article appeared in the Autumn issue of CampdenFO. Not long after the magazine went to print Doug Tompkins, whose foundation is mentioned in the text and whose wife, Kris, was interviewed for the article, died suddenly in a kayaking accident. Despite being a serial entrepreneur (he founded The North Face and co-founded Esprit), his philanthropy and commitment to conservation is one of the greatest legacies he leaves behind.

At the age of 21, Paul Lister shot his first deer in a cull in Scotland. “When you do that, that really makes you wonder why it is necessary,” Lister says. “When you realise how much the landscape has been altered, so much so that we need to cull deer, as opposed to their natural predators – which are wolves obviously – then you become interested in parts of Europe, where the landscape still has large carnivores.”

Where wolves, bears, and trees once ruled, the Scottish Highlands are now controlled by a handful of individuals – less than 500 own half the private land in Scotland (a concentration the Scottish National Party is currently trying to dismantle through the land reform act). In 2003, Lister, whose father founded British furniture chain MFI Group, bought a 23,000-acre property, but rather than a hunting playground, it would become Alladale Wilderness Reserve. Most notably, from the national media's perspective, he wants to return apex predators to the ecosystem (the wolf population became extinct in Scotland in the 18th century).

A missing link in the local ecosystem's ability to manage itself is a predator, says Alexandra Kennaugh, executive director at The European Nature Trust, Lister's foundation (deer numbers have trebled in the last 50 years to an estimated 750,000). “Reintroducing a wolf into the ecological equation would bring balance back to the natural system, where we now have to aggressively manage the land.” Kennaugh says a deer predator could give the local woodlands a chance to grow – and be an economic opportunity for the Highlands.

For all humans' interest in the demise of dinosaurs it is notable that the current Holocene extinction, as it's named, has not captured the public imagination. The current rate of vertebrate extinction is 100 times greater than it should be, according to a paper released by scientists from Princeton, Stanford, and the University of California in June (they deliberately took a conservative approach, not wanting to be accused of being “alarmist”).

But never mind the existential sadness that comes with species extinction, humans are on course to kill many biodiversity benefits (think crop pollination or water purification) in as little as three human lifetimes, the paper, published in Science Advances, stated. Consider Switzerland, where 17% of forests are managed to stop avalanches, a service worth more than $2 billion, according to figures from the World Commission on Protected Areas. Protected areas of the Brazilian Amazon are likely to prevent 670,000 square km of deforestation by 2050, which would capture 8 billion tonnes of carbon.

Despite species' extinction, despite climate change, environmental philanthropy accounted for a measly 4% of all charitable giving in the UK, according to last year's Where the Green Grants Went (the US is half that, according to the Atlas of Giving). A quarter of family offices contribute to environmental philanthropy, according to The Global Family Office Report. Biodiversity and species preservation accounted for just under a quarter of environmental giving in 2011/2012, but it was down three percentage points from the year before. Energy, the quickest growing cause, saw an almost four fold increase over the same period.

Because so much philanthropy is targeted towards humanitarian causes, Lister says he wanted to focus on the environment. And since so much of that philanthropy is focused on Africa and the Amazon, he decided he wanted to concentrate on something closer to home. The Convention on Biological Diversity, signed in Aichi, Japan in 2010, has set a target to protect 17% of terrestrial lands by 2020, and 10% of marine ecosystems. Increasingly, deforestation, pollution, poaching, and intensification of agriculture mean that numerous plant and animal species are only found inside protected areas, the Protected Planet report by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) and UN Environment Programme says.

As well as restoring Caledonian forest ecosystems in Scotland (pictured right), The European Nature Trust is focused on the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. “Not that I'm looking for people to stop spending their money on good causes to do with disease or childcare or disasters, I would just like to see more people giving, and more people giving to the environment.” The convergence of social and environmental issues is evident through humanitarian organisations like Oxfam, which are increasingly addressing issues like climate change through their work. Despite doing the least to cause it, poor communities are feeling the full force of climate change, the non-profit says.

As well as restoring Caledonian forest ecosystems in Scotland (pictured right), The European Nature Trust is focused on the Carpathian Mountains in Romania. “Not that I'm looking for people to stop spending their money on good causes to do with disease or childcare or disasters, I would just like to see more people giving, and more people giving to the environment.” The convergence of social and environmental issues is evident through humanitarian organisations like Oxfam, which are increasingly addressing issues like climate change through their work. Despite doing the least to cause it, poor communities are feeling the full force of climate change, the non-profit says.

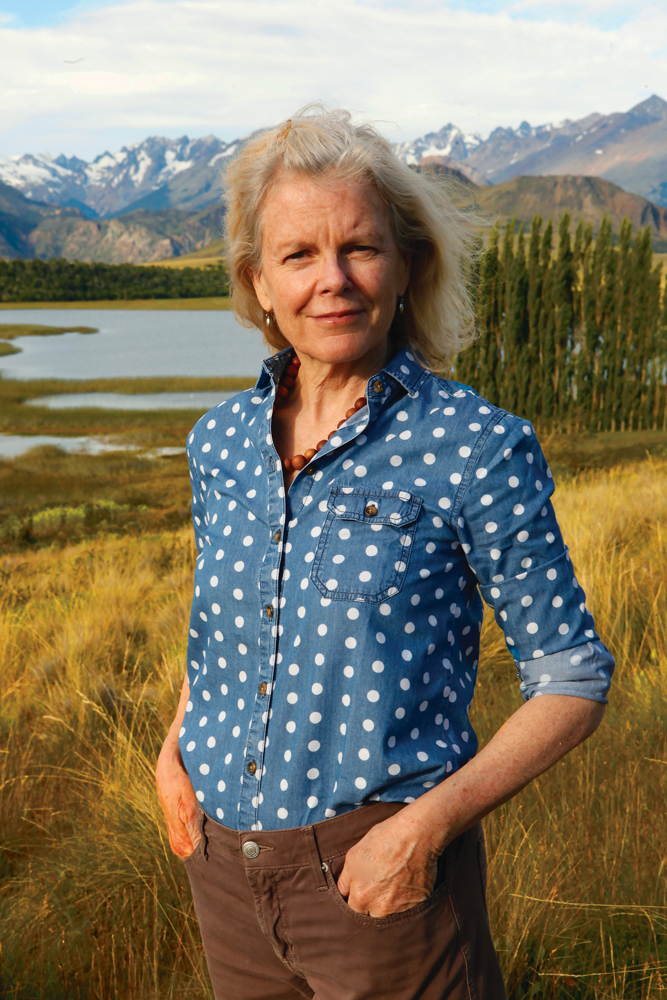

“Key habitat is a masterpiece. Just like a Picasso, or a Turner, or a Hopper painting, these are masterpieces,” says Kristine Tompkins, who with her husband, Doug, has purchased 2-million acres across Argentina and Chile for conservation purposes, creating five national parks with another five to go. Tompkins says she knows other environmentalists who have poured millions into climate change lobbying only to be disheartened. “If they spent that kind of money on conservation and putting key habitat together, you are creating petri dishes for biodiversity all around the world.”

Tompkins was long-standing CEO of outdoor clothing company Patagonia. Her husband Doug co-founded another outdoor company, The North Face, as well as fashion company Esprit (a former CFO now works in the Tompkins family office). Tompkins' second career, as CEO of Conservación Patagónica, is incredibly varied. “I can be checking jaguars, pumas, working with biologists, working with partners, other funders, giving talks, working with our administrators in the various projects, working on budgets, or checking budgets.”

Her experience at Patagonia Inc was pertinent to the work she is now doing in the national parks. “There are skills you take from your business life and you apply those to getting things done in your conservation life,” Tompkins says. “You have organisational skills, you know how to build teams, you know how to manage budgets. You perhaps have a personality that's more results driven than you might have without those experiences.” She remains on the board at Patagonia, and says she loved working at the company, but had an unshakeable feeling she needed to do something else with her life.

Land conservation and restoration is one of the oldest environmental philanthropy traditions about, with John D Rockefeller Jr's contribution to Grand Teton National Park one of the earliest examples (the UK's New Forest, a national park since 2005, has been under some form of protection since 1079, when William the Conqueror wanted it preserved as a royal hunting ground). Wildlands Philanthropy: The Great American Tradition, published by the Foundation for Deep Ecology, one of the Tompkins' foundations, profiled US philanthropists protecting their little corners of the planet, ranging from a 10-acre island in Maine to the Tompkins' work on Corcovado (726,000ha) and Monte León National Parks (62,168ha).

According to Phil Tabas, special adviser with US environmental organisation The Nature Conservancy, motivations behind people picking their chosen spot for land conservation philanthropy is often down to their interests and their own associations with the geography. According to Dr Laura Miller, executive director at environmental research and funding organisation Synchronicity Earth, this can lead to an unsystematic way of addressing the areas in most need of this type of philanthropy. Only 22% of the world's most threatened species populations lived in completely protected areas, according to 2008 figures from the Alliance of Zero Extinction, and 51% had no protection.

The bulk of protected areas spending is publicly funded, but this funding is decreasing. In Latin America and the Caribbean, where there is a $300 million-plus gap in spending, national governments pay 58% of the annual management budget of protected areas, and international assistance (public and private) pays 16%. Indigenous and community conserved areas (ICCAs), whereby local communities that have long lived sustainably off the land take ownership in its conservation, complement public and private efforts in land conservation and have built momentum over the last decade.

“People think that the 2-million acres we've purchased and put into permanent conservation is a lot of land, and by most standards it is; but it's a drop in a very large bucket when you think about the number of hectares that are being converted for use on the other side,” Tompkins (pictured left) says, adding: “There cannot be too many conservationists in the world, and in fact the contrary is true: there are painfully few.” Of all the crises facing the planet, Tompkins argues extinction of biodiversity is the most profound, the most urgent.

“People think that the 2-million acres we've purchased and put into permanent conservation is a lot of land, and by most standards it is; but it's a drop in a very large bucket when you think about the number of hectares that are being converted for use on the other side,” Tompkins (pictured left) says, adding: “There cannot be too many conservationists in the world, and in fact the contrary is true: there are painfully few.” Of all the crises facing the planet, Tompkins argues extinction of biodiversity is the most profound, the most urgent.

The role of private philanthropy – including charities, corporates, and ecotourism, as well as families and individuals – was a focus at the 2014 World Parks Congress in Sydney. “Private land conservation has a crucial role to play in biodiversity protection. Increasingly there is recognition that government action – whether through regulation or acquisition of protected areas – is not enough,” says Laura Johnson, director of the International Land Conservation Network, which was officially launched one year after the congress. It has begun to address some gaps raised then, including launching an international census of private land conservation organisations.

Tabas says there are various options for people interested in land preservation from a national park, to a land trust to, in the US, conservation easements, where the land can still be used by private landowners but in a way that is keeping with the environment. “There are conservation possibilities everywhere, and they come in every size and scale and condition,” Tompkins says. “Some are pristine, some are badly damaged and merit restoration. The truth is it's easy to find projects to take up.”

Wolves are the first apex predator Lister plans to return to the Highlands in a fenced reserve that must be at least 50,000 acres, followed by bears. “We really started the ball rolling in 2004 when I went public with the idea,” Lister says. The proposal to reintroduce predators startled locals, and the media ridiculed Lister's idea as eccentric. “It was shocking in those days. It was like 'Oh my god, how unbelievable, this guy is crazy',” Lister says about the reaction. But media coverage is changing – a recent double page spread in Scotland's Herald Sun featured wolves howling to the sky, rather than aggressively gnarling their teeth at the camera.

“Our vision for revitalising tourism will be a benefit for the community. Instead of just saying 'we've got a pot of land and we're going to use it for our mates to go out and have fun'.” The reintroduced white-tailed eagle has generated £5 million ($7.7 million) of tourism dollars annually in Scotland, and in total wildlife tourism brings in £276 million. Lister says wolves and bears could add much more.

Fellow conservation philanthropist Ben Goldsmith says he likes the fact Lister has sparked a debate, adding that the Scottish Highlands have a population density of about nine people per square kilometre, whereas somewhere like Vancouver Island in Canada has around three times that and people live “perfectly comfortably alongside wildlife” – thousands of cougars, coyotes, and bears. “There is no country on earth that has more successfully eliminated its wildlife than Great Britain,” says Goldsmith.

It's not just wildlife, but the public imagination that is being stripped bare. This year the Oxford Junior Dictionary replaced words like acorn, ash and newt with chatroom and broadband. “As a modern society we're just massively disconnected, we put nature at a really far reach,” says Miller, whose organisation researches gaps and priorities for environmental grants, creating funding portfolios for philanthropists. She points to mechanised agriculture. “We don't realise how much things like our food systems are part and parcel of the extinction crisis, so deforestation, overfishing, algal blooms, these are by-products of our own systems.”

Miller emphasises that public engagement needs to go in tandem with protected lands efforts, pointing to the Virunga National Park, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, which is currently threatened by oil exploration – even though it is a Unesco World Heritage Site. In 2010, the New Zealand government backed down on proposed mining in some of its most pristine national parks following overwhelmingly negative feedback, which shows the power of public engagement, Miller says (the same government just recently announced it would create a marine reserve the size of France – the Kermadec ocean conservancy). The successful emergence of indigenous peoples' and community conserved areas is another example.

This year's Science Advance paper detailing the sixth great extinction remarked that habitat loss, overexploitation for economic gain, and climate change were all related to human population growth, which results in increased consumption – especially among the rich. “How much money, how many properties do you need, how many cars do you need?” asks Lister (pictured right). “At what point does a family decide it has enough wealth to live on for the next two generations that they start to employ their resources and their time and energy and expertise to doing something that is part of the solution, not the problem.”

This year's Science Advance paper detailing the sixth great extinction remarked that habitat loss, overexploitation for economic gain, and climate change were all related to human population growth, which results in increased consumption – especially among the rich. “How much money, how many properties do you need, how many cars do you need?” asks Lister (pictured right). “At what point does a family decide it has enough wealth to live on for the next two generations that they start to employ their resources and their time and energy and expertise to doing something that is part of the solution, not the problem.”

In South America Tompkins has been witness to the release of Andean condors and seen giant anteaters flourish. She says walking through recovered grasslands in the national park is an almost emotional event. “There is nothing more satisfying than walking across land you helped preserve forever. Every blade of grass you cross, every tree you walk by, every stream you have to cross is something that from that day forward will only improve in quality. The ecological quality, the species that live in that area, regardless of what it is, will not be diminished further than it is now.”

A highland scene

Paul Lister hopes to stimulate Scotland's wildlife economy when he returns predators to the landscape – but his reserve is already open to guests.

Howling wolves (sculpted not real) welcome us to Alladale Wilderness Reserve's Victorian shooting manor, which is large – seven double bedrooms – but not imposing. Plaid carpet leads us to the living area's crackling fire. Delicious pear and almond cake with tea gives our stomachs a chance to settle after the windy country roads on the way from Inverness Airport.

Paul Lister, the laird who has spent the last decade restoring the denuded 23,000-acre property, says he welcomes would-be philanthropists to the lodge. When he arrives about 30 minutes after us, he is certainly brimming with enthusiasm for his wildlife and forest conservation plans. Atop the piano, there are photos of the Lister family, and while there are two secluded “bothies” (cottages) available to rent in dramatic scenery 10 minutes walk away, the lodge feels like being welcomed into a home.

Without even leaving the lodge's pristine green lawns (the reserve gets much more wild in the glens and lochs beyond) around six deer traipse by as I unpack in my double room. But our real tour will start the following day, with our guides, local Scot Innes MacNeill and his redheaded sidekick, a young Labrador, Lincoln. The tour of the landscape is vast and rolling (although the drive in the 4x4 is much bouncier).

Wolves are not yet at Alladale, but the rotund and shaggy blond Highland cattle are charming – and equally curious of us as we are of them, as we step out with our cameras and our wellies to meet them. A baby deer (MacNeill thinks only a couple of days old) spotted by monocular scrambling up the hill is another highlight. There is human history too. Stoney rubble is all that's left of the Crofter houses – small-scale farmers who were victims of the English in the Highland Clearances. We later take an afternoon walk to see the church that kept them refuge – their names literally etched into history in its windows.

Alladale Main Lodge can sleep up to 14 and comes with a commercial kitchen, gym and sauna, and billiards room. Activities include trout fishing and mountain biking, 4x4 safaris and ranger walks, as well as deer stalking (to manage numbers). Prices start from £150/person.