Past time

Legend has it that when the Brazilian Alberto Santos-Dumont, an early pioneer of powered flight, was getting to grips with aeroplanes back in the early 20th century he rather sensibly decided he needed a timepiece that he could read without taking his hands off the joystick.

He turned to a friend, the watchmaker Louis Cartier, who duly made him an ingenious watch that could be worn on the wrist, meaning that the intrepid pilot could glance at the time without risking life and limb. It was a revelation in the days when pocket watches ruled. True, Swiss watchmaker Patek Philippe had previously made a wristwatch for men, adapting a feminine fashion that had been around for years, but it was the Cartier effort that introduced the idea to Paris, the capital of world fashion then as now, and gave the watch the masculine glamour that it has to this day.

The market for collectible watches is largely a male domain, perhaps because they are, in many parts of the world, one of the few pieces of jewellery that are acceptable for a man to wear. Collectors abound, and include the actor Michael Douglas and Russian president Vladimir Putin. Watches evoke emotion too. “A rare watch is like a piece of artwork, or a classic car,” says Samuel Olsson, founder and director of International Watch Fairs, a global platform for the watch trade. “It provokes the same passionate, emotional capitalism in people who want to collect them and invest in a tangible asset.”

The modern trade in luxury watches can be dated to 1980, when Sotheby’s held a trial auction in New York. At the time mechanical watches were on the decline after the introduction of the quartz watch, while the appeal of collectible, second-hand watches had yet to develop. But this didn’t take long – and despite the financial crisis, the watch market continues to boom.

“There has never been so much money spent on advertising for luxury watches and so many brands around – business seems to be booming as people search for alternative safe-haven investments with gold recently reaching record highs,” says Olsson. In 2010, auction house Christie’s watch sales totalled $91.2 million (€67.4 million), the highest-ever annual sales total for fine watches. Aurel Bacs, the international head of its watch department, says that being relatively young at just 30 years, the watch market “still has a lot of potential for growth. It has also shown a great deal of resilience in the current economic climate”.

So what should you be looking for? For a start, the right brands. While some brands rise and fall with fashion, others remain perennially popular, such as Rolex, Patek Philippe, Omega, Vacheron Constantin, Audemars Piguet, Longines, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Cartier, Tissot, Breitling and TAG Heuer. And you don’t have to invest a huge amount to get involved in watches. Pieces start at around €500 for a watch at auction and reach as much as €200,000 or more for a rare timepiece. “Watches are popular along the entire investor spectrum as they are available at a range of price points,” says Bacs.

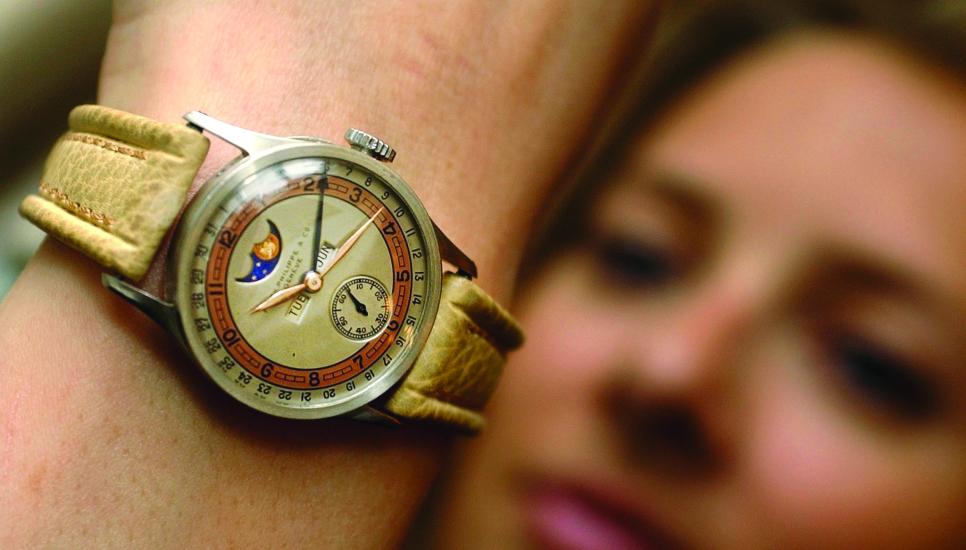

However, some brands are more sought-after than others. Patek Philippe is, according to Bacs, the Rolls-Royce of the watch world. It also trades heavily on its image of tradition. A family-owned business founded in 1839, it prides itself on its Swiss heritage. “Patek Philippe has an established manufacturing tradition and a strong brand philosophy which watch collectors appreciate,” says Bacs. Among the classics is the Patek Philippe Nautilus. This was first introduced in 1976 with a design inspired by the shape of a porthole. Rarity also plays a part in Patek Philippe’s high prices – in 2010 it made just 40,000 watches.

Any list of the most expensive watches sold at auctions will feature several Patek Philippes. The highest price achieved for a wristwatch at a Christie’s sale was for a unique, historically important gold perpetual calendar chronograph Patek Philippe wristwatch. Manufactured in 1943, this sold in Geneva in May 2010 for SFr6.25 million (€5.05 million). At another Christie’s sale in Geneva in May this year, a rare Patek Philippe watch achieved a world record price for a simple chronograph at $3.6 million.

On the other hand, Rolex became famous thanks to its pursuit of innovation. It was the first manufacturer to produce watches with automatically changing day and date indictors. Rolex also profits by its connection with a famous fan. In the James Bond books, Ian Fleming gave the secret agent a Rolex watch, and the brand has been associated with him ever since, boosting Rolex’s popularity. The spy sported a Rolex Submariner – a pioneering waterproof watch – in many of the films. This pedigree and the sporting image mean that they are “always popular with an international clientele”, says Bacs. A Rolex was also behind one of the most exciting auction sales, says Kate Lacey, a watch specialist at Bonhams. “The highlights are often the sales where the vendors had no previous idea that their watch was of value. One such sale was a very rare Rolex that had a very rare dial,” she says. “The story is that a friend of [the watch owner] who happened to know about watches spotted their watch at a dinner party and mentioned that they might want to get it checked at Bonhams, and it eventually sold for £81,000 (€94,414),” she says.

Part of a watch’s value comes from the materials it is made of, but not as much as novices might think, and gold watches are not necessarily more valuable than steel ones. Typically, when watches were bought in the 1920s to 1940s, a special timepiece was considered a luxury item. The idea of the wristwatch as an indulgent purchase saw them traditionally cased in a precious metal. But as with all collectibles, rarity defines price at auction, and steel is the less common casing for many watch types.

Of those which are made of precious metals, yellow gold is most common, followed by pink gold then white gold, with steel and platinum the rarest. However, during hard times, such as the Great Depression and the years following World War II, watches were cased in steel because gold was unaffordable. Perhaps surprisingly, age is often not a big factor in a watch’s value at auctions. Maker, model, condition, complications and rarity are the main elements.

As a general rule, the more complications – functions in addition to telling the time – that a watch has, the more valuable it is. Complications can include displaying the date, day and month – “chronograph” refers to a watch having a stopwatch facility. “The reasons that such additional functions add to the value of a watch is that greater workmanship is involved and such complexities mean that fewer watches are produced,” says Bacs.

The provenance, or wearable history, of a watch can also add to its value. There are many different types of watches that appeal to collectors, says Lacey, with the most popular vintage pieces having an interesting provenance, while newer models are often limited edition pieces or discontinued ranges. “Wristwatches with military provenance are particularly strong sellers, as are diving watches,” she adds.

There are basic methods collectors can use to check a watch’s condition. For instance, to see if the glass is scratched, or the crown – which is turned to adjust or wind the watch and can become worn – is in place and works. Both can be replaced if needed, but doing so will impact dramatically on a watch’s value if the time comes to sell it. Collectors should also be aware that the watch market is magnet for counterfeiters. In recent years, watchmakers in India and China have produced pieces that are almost impossible to distinguish from the real thing. The help of a reputable dealer to begin your search will set you on the right track, and help you to avoid falling victim to fraudsters.

Potential investors should always ask for a certificate of authenticity and a history of any restorative work. Fortunately, many of the brands you are likely to find at auction, such as Patek and Vacheron, have historical archives that date back centuries and can be checked. “Buyers are becoming more and more particular about their purchases with an increasing demand for documentation and paperwork,” says Lacey. To evaluate a watch, an in-house specialist at an auction house will look at it free of charge. Alternatively, buyers can check auction house websites for watches according to their favourite makers and styles, where they can also find information on past sales, illustrating the majority of the sold lots.

As with all collectibles, investors need to check tax and import regulations in their particular jurisdiction. “Also remember that some watches are subject to import laws and charges and cannot be exported – Rolex watches, for example, cannot be imported to the US – so check before you buy,” says Lacey. The good news is that watches are exempt from UK capital gains tax as they are considered a “wasting asset”. “So if a watch increases in value, there is no CGT to worry about when later selling it, but the bad news is that if the sale makes a loss, the loss cannot be offset against gains made in respect of other assets,” says Simon Leney at UK-based Cripps Law. “This adds to the risk factor relating to the investment - if the investment does not perform, there is no silver lining in the form of a tax loss to set against future taxable gains elsewhere,” he says.

In the UK, the other tax that might crop up as an issue is inheritance tax. A collection can be worth a hefty sum and to avoid IHT on death, an investor might choose to give away or sell in their lifetime some of the collection. “That will reduce its value in hand and thus the amount of IHT on the collector’s estate,” says Leney.

Of course, anyone choosing to establish a watch collection needs patience if they are to produce profit from this over the long term. The market for collectible watches is very illiquid as valuable timepieces are either passed on from one generation to the next or can only be bought and resold at auctions. Some serious research is needed before you dip your toe in the water, and the best way is to go to the international auctions held throughout the year. There is no requirement to bid and this will help prospective collectors get an understanding of how the process works and explore their particular passions.

As with any luxury item that you are going to buy as an investment, everybody advises that you only splash out on watches that you love and can enjoy for years before you trade it in. After all, this is a market for enthusiasts. “It’s vital that an investor buys watches that they personally find interesting and that they start slowly, building up their knowledge through reading, attending auctions, physically holding and inspecting as many watches as possible, and talking to those who work in the field,” says Bacs. Which sounds as good a way as any to fire those passions.