Coming of age

The new generation of ultra-high net worth family members wants to do more than just see their fortunes grow. A new study by OppenheimerFunds and Campden Research has found that these 'Millennials' want to make a dent in the world's problems, but not the way their parents did it.

When you have been named the world's youngest self-made billionaire, what can be more worthwhile than using your wealth to make the world a better place? That was what Dustin Moskovitz thought when he set up the Good Ventures foundation with the billions he made as one of Mark Zuckerberg's Facebook co-founders.

Describing itself as “a philanthropic foundation whose mission is to help humanity thrive”, the organisation has, since its creation five years ago, put money into projects in such diverse fields as animal welfare, criminal justice system reform, and biomedical research. A for-profit investment arm created in 2012 generates funds for the charitable ventures.

In channelling his money into worthwhile causes, the 31-year-old Moskovitz is following a pattern seen among many ultra-high net worth “Millennials”, those born between 1980 and 1995. The importance to this generation of using wealth to make a difference is highlighted in Proving Worth: The Values of Affluent Millennials in North America, an OppenheimerFunds and Campden Research study of young North Americans from families with net worths greater than $35 million.

“The first big finding was this desire to do good with their money; a major focus was on philanthropy and impact investing,” says Ned Dane, senior vice president and head of OppenheimerFunds' private client group.

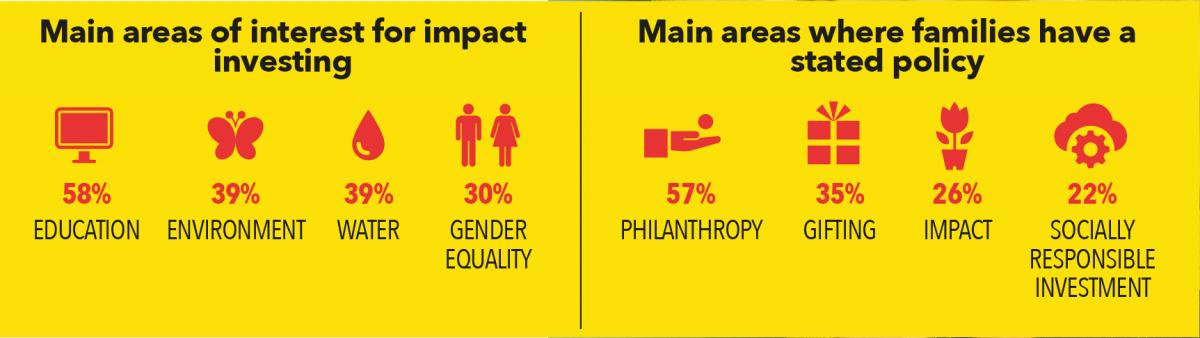

“What rose to the top were things that had to do with ... improving the human condition — providing better education, better living conditions and clean water, as well as gender equality-type issues.”

While Moskovitz and his wife, Cari Tuna, are set on giving away their riches, most Millennials interviewed for the study want to retain their wealth while sharing this aim to do good. This is unsurprising given that in some cases it has been built up over six generations. They are anything but dissolute youngsters who will fritter away their inheritance through a focus on only themselves: nearly nine out of 10 consider family wealth preservation as important or very important.

Moreover, having come to maturity at a time when yesterday's certainties have been replaced by a climate of financial strife, affluent Millennials tend to be more conservative in investment decisions than their parents. Parallels can even be drawn with the Silent Generation, who were born from the 1920s to the early 1940s.

“They're attitudinally more akin to the children of the Great Depression. They're keenly focused on preserving wealth ... and they're very averse to taking risks,” says Dane.

A key part of the altruism of Millennials centres on impact investments, which aim to produce a measurable environmental or social upside, as well as a financial return.

“For this generation, it's, 'What is this doing and what sort of improvement am I providing with this investment?',” says Dane.

Indeed the family office of one Millennial, Ginny, a late 20-something fifth-generation member of a Californian family, now puts all of its funds into impact and socially responsible investments.

“After learning about investments and being given a greater role in the family office, we've been able to align our capital with things I'm interested in,” she says. “No one in our family has negative or ambivalent opinions about impact investing.”

Even when following strict policies linked to environmental, social and governance issues and socially responsible investments, she says it is possible to have a portfolio with the required diversity.

Even when following strict policies linked to environmental, social and governance issues and socially responsible investments, she says it is possible to have a portfolio with the required diversity.

Ginny's case is not unusual: when portfolios are focused on impact investing, Millennials tend to be closer to the decision-making process. But in other families, the younger generation is more likely to be kept at arm's length.

“The first place where they might touch their family wealth is sitting on the board. If there's a family office or a family foundation with an investment committee, they're starting to be involved as a member of that committee. They feel their voice is being heard, but they're not decision-makers,” says Dane.

Although typically not decision-makers yet — less than one-fifth make strategic decisions about overall wealth management — Millennials are already building relationships with advisers and often they look for people who will stay with them long term. They need this outside expertise even though, in the words of Dane, “they are better educated than any generation before them”.

“They have more access to knowledge in real time ... they very much live in a digital network world with Facebook and other things that let them be communicated with virtually. Even though they love that way, they really value personal advice to bridge that gap between awareness and knowledge,” he says.

For some affluent Millennials, advisers are needed for the basics: a knowledge of how the financial world works. The time invested by advisers in this can pay dividends.

“We had one woman who met with her adviser once a week about broad financial topics. She needed help with banking and insurance and lending,” says Dane. “The family adviser took the time to work with her on her terms. He was very well positioned to be her adviser in the future.”

Rather than being offered one-size-fits-all solutions, Millennials expect advisers to make the effort to get to know them properly, to understand their priorities and how these can be achieved. Family office executives are the primary adviser for a quarter of respondents, while private bankers (13%) and independent consultants (13%) are also important. Commercial banks and wirehouses are less significant when it comes to helping Millennials shape their goals.

Frank, a 30-something from the American midwest married to a fourth-generation family member, exemplifies the way in which many young family members seek a “high-touch” personalised service with regular face-to-face contact. At the very least, advisers should keep in regular email and telephone contact with family members.

“We expect advisers to be socially aware of our family, our goals, and values. We expect them to naturally look out for opportunities for the family, regardless of whether or not they get the assets under management from us,” says Frank.

“About a decade ago, we seeded a venture capital fund after a liquidity event. The two managers we used for that event have become like consiglieri beyond their initial role. The positive experiences we had with them made us trust them,” he adds.

The research highlighted important areas where Millennials seek guidance, but in which advisers may lack expertise. Key among these are how to equitably distribute wealth to the next generation, and resolving family conflict, an area that is much broader than just investments.

“It gets into family dynamics. For some families, it's an area they've spent a bit of time on; for others, it's new ... There's a huge disparity between their interest in having advisers engage with this and the level of expertise advisers have,” Dane notes.

Despite the challenges, there is much to be upbeat about, he says. Advisers can “connect the dots” for Millennials, building better outcomes for this next generation of ultra-high net worth family members. And who knows whether they decide to preserve, grow or put their capital into helping improve the lives of others - just as Dustin Moskovitz is doing.