Funding social impact since 1672

The family behind England’s oldest privately-owned bank have been giving to charitable causes for more than three hundred years. Now, both its principal and millennial scion are investing their time and talents into a fresh initiative to support early-stage social enterprises at the grassroots, where the need is greatest.

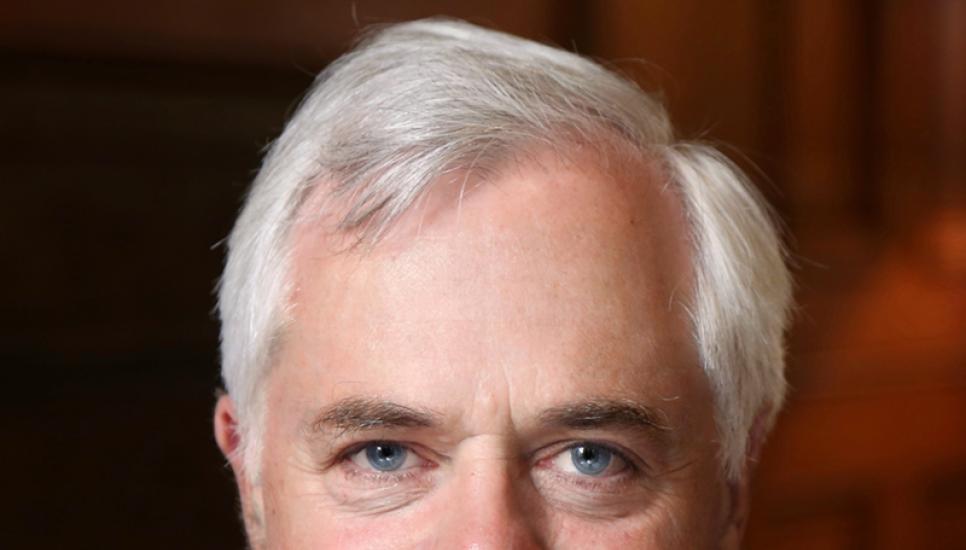

Alexander Hoare, 57, is the eleventh-generation partner and director of the British banking dynasty C. Hoare and Co., and the award-winning keeper of the flame of the family’s philanthropic traditions, which date back to the bank’s foundation in 1672.

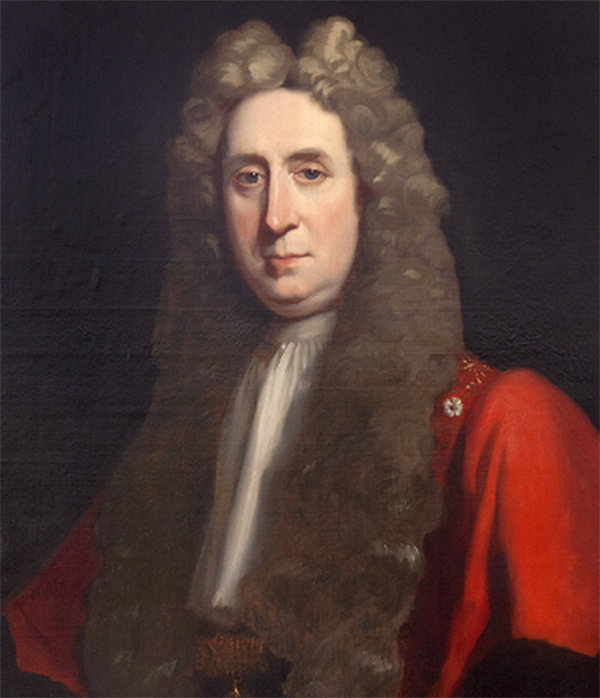

A patron of Royal Trinity Hospice and a founder partner in the impact investment partnership Project Snowball, charity begins at home with Hoare in his role as trustee of the family’s own Golden Bottle Trust. The charitable trust was set up by the partners of the bank in 1985. The trust was named after the sign that Sir Richard Hoare, the family business founder and father of 17 children, once hung outside his bank’s original goldsmith’s business on the City of London’s bustling Cheapside.

Alexander Hoare says the family bank tithes to the family trust, which has granted more than £22.8 million ($29.8 million) since its foundation to a wide range of causes, from education and health, to environmental sustainability, and social investment. In the year to September 2017, the bank donated £7.2 million to the trust which made £1.7 million ($2.3 million) worth of grants to 344 beneficiaries, 27% of whom were new recipients.

The Golden Bottle Trust was not the family’s first foray into formalised philanthropy. Alexander’s fellow tenth-generation cousin, Richard Q Hoare, founded and originally chaired the Bulldog Trust two years earlier in 1983. The Bulldog Trust continues to support and advise charities facing immediate financial difficulties with Richard’s son, Charles, as chairman since 2013.

“We wish to be good bankers and good citizens, so that should hopefully inspire young staff and young customers, and guide management,” Alexander Hoare says, from London’s Two Temple Place. The neo-gothic mansion on the UK capital’s Thames Embankment was bought by the Bulldog Trust for its headquarters in 1999.

“Why do we want that? Because it has worked jolly well for 300 years. We have done a lot of giving, a tremendous record going back, so I believe what goes around comes around.”

“Why do we want that? Because it has worked jolly well for 300 years. We have done a lot of giving, a tremendous record going back, so I believe what goes around comes around.”

Philanthropy’s angel investor

The Golden Bottle and Bulldog Trusts became founding partners of The Fore in 2017, with C. Hoare and Co. as one of its core funders and Golden Bottle donating £300,000. The mission of The Fore is to open access to funding and professional expertise for exceptional young social enterprises by bringing together funders who otherwise work alone. The Golden Bottle Trust became a venture capitalist in philanthropy with The Fore dedicated to funding start-up charities.

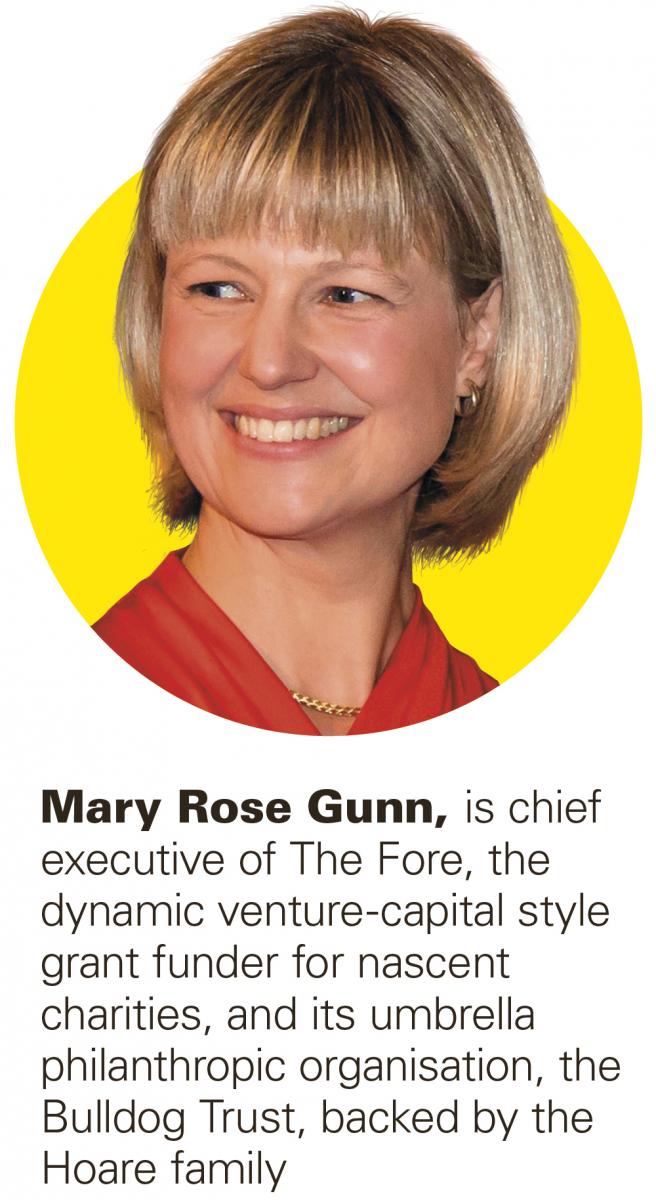

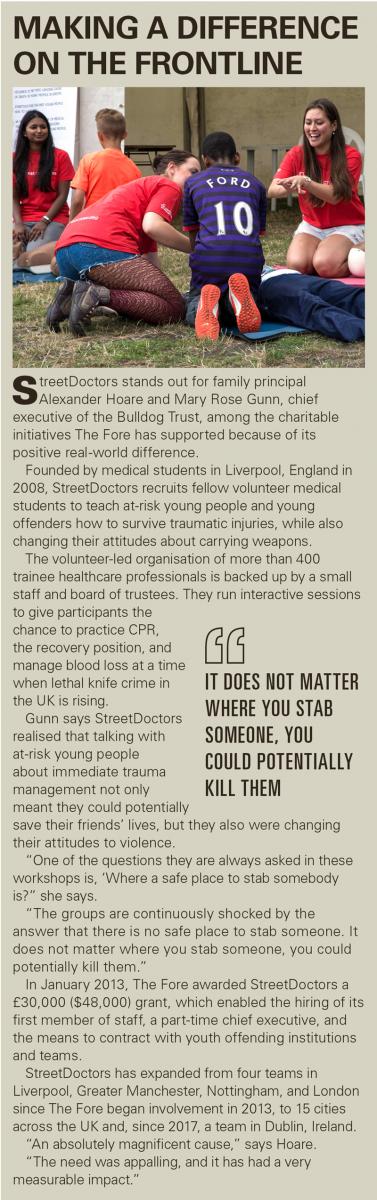

Mary Rose Gunn, chief executive of the Bulldog Trust, says The Fore “is about finding exciting, smaller, earlier-stage organisations. That means charities and social enterprises, where the money that we give makes a tangible difference and creates transformational change within the organisation.”

Hoare says some traditional giving does good, but quite a lot does not.

“Where it goes well for both the donor and donee is if you get engaged and you start giving time as well as money and experience and contacts and connections, then giving money can be very powerful,” he says.

“We saw this opportunity with The Fore where the Bulldog Trust has this fabulous network of professional contacts, people willing to give time and expertise. We had cash which was not reaching the smallest, best, neediest charities in the land, and so there was quite a natural coming together, especially as we knew each other.”

The Fore runs three 12-week funding rounds to coincide with the academic calendar each year. Thousands of applications are made for each funding round, but Gunn says, unlike most other funding bodies, The Fore is “sector and geographically agnostic” and is in the mindset of looking to provide small business loans.

“We keep the filter very open because it means that we can get the organisations that are run by the best people who are going to spend our money most effectively,” she says.

“Whereas when you have quite specific criteria, which a lot of funders do, when you’re working with small charities, it means that essentially you end up funding charities that have the best fundraisers because they know how to navigate your systems.”

Of a typical 100 applications for development funding and strategic advice at The Fore, 30 go to the due diligence stage. About 5% are proposed for funding and the top 3% end up being funded. A point of difference is that The Fore’s funders, including the Hoare staff and family, are sitting on those funding panels and making the final decisions. Applicants who are not funded are given helpful feedback.

Of a typical 100 applications for development funding and strategic advice at The Fore, 30 go to the due diligence stage. About 5% are proposed for funding and the top 3% end up being funded. A point of difference is that The Fore’s funders, including the Hoare staff and family, are sitting on those funding panels and making the final decisions. Applicants who are not funded are given helpful feedback.

Approved start-up charities are awarded grants of up to £30,000 over one to three years. As part of The Fore’s assessment process, applicants are required to suggest some organisational key performance indicators (KPI) for The Fore to judge the success of its funding against.

“Those KPIs are discussed and honed with their assessors, so they are not overpromising and not underpromising, and it means our funding ends up completely aligned,” Gunn says.

“We check in with them officially once a year and we score them against their success rate. For funders that is particularly valuable because it means they can see an update on how the money has been effectively used and spent.”

For its low-bono application assessors, The Fore taps into the under-utilised talent, expertise, and professionalism of people who are retired, on a career break, or pursue portfolio careers, Gunn says.

Those assessors, among them a chief operating officer of a Swiss private bank and an economics lecturer at Oxford, give start-up philanthropists the benefits of their strategic advice to achieve the best sustainable impact for both the applicant and The Fore.

Millennial expectations

The Fore sees a growing need from small-scale charities for more funding, yet the public are inclined to donate to the big brands in the charity sector. Gunn says it is the “harshest irony” that people give to the multinational organisations because they feel they can trust them to put their money to good use, despite the fact it is the major players which have been rocked by scandal. Oxfam GB was banned from operating in Haiti last year after its staff were accused of sexual misconduct following the 2010 earthquake.

Hoare says up-and-coming generations are also having an impact in philanthropy.

“They are no longer satisfied just to be seen giving money. They want to see the money is doing good. They want measures of impact, or they want to engage personally, or ideally they want to invest for social and financial returns,” he says.

“They are no longer satisfied just to be seen giving money. They want to see the money is doing good. They want measures of impact, or they want to engage personally, or ideally they want to invest for social and financial returns,” he says.

“Quite often, older trustees have not got a clue how the next generation is thinking and it is quite a challenge to take them on to a new way of thinking. The Fore is a nice way they can see social impact is not risky, it is a sensible way of doing contemporary philanthropy.”

The Fore is also enabling millennial members of the Hoare family to gain practical experience in this type of philanthropy. Rennie Hoare, 33, the bank’s head of philanthropy is the most recent addition to the crop of 11th generation partners. He oversees the philanthropic activities of the family, staff and customers and through his family’s investment in the Golden Bottle and Bulldog Trusts, joined The Fore. He sits on its investment committees and participates in the network of members who connect with the organisations they are especially interested in.

“Rennie is better trained than I ever was in the field of philanthropy,” Hoare says of his fellow partner.

“He is a very committed member of The Fore and wants to get stuck in at a more personal level than just writing a cheque.”

Gunn says Rennie is one of their best “graduates”. He has used his time on the committee to further understand the wide range of organisations working in a variety of areas to solve a huge number of issues.

When it comes to modern philanthropy, “families, family foundations, family offices, and family trusts are in good positions to take risks,” Alexander Hoare says.

“It is pretty hard to get a bunch of fiduciaries and a quango to do something new, for all sorts of vested interest reasons. But a family that has made their money making widgets can equally well give the money away in an innovative way, which may or may not work. It is risky, but all progress results from unreasonable people taking risks.”