Bidding 24/7: The world of online art auctions

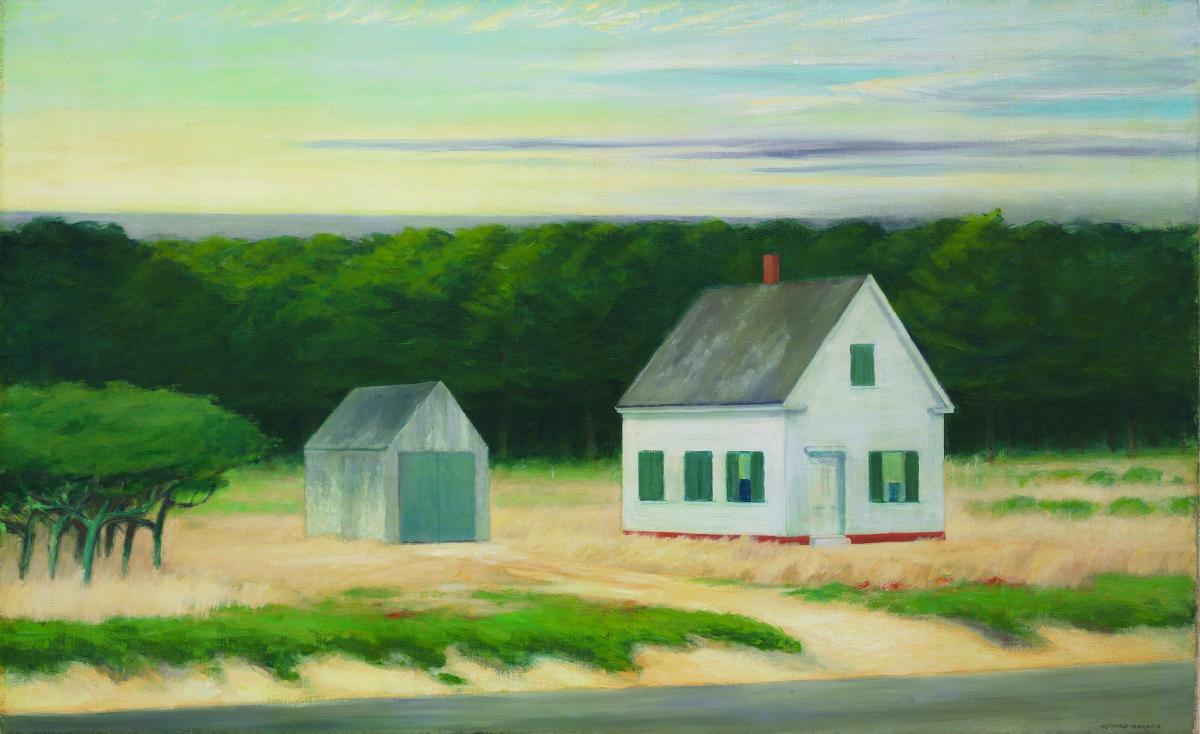

In December of 2012 Edward Hopper’s painting October on Cape Cod (pictured, below right) was sold at auction by Christie’s for $9.6 million (€7.1 million). Nothing unusual about that, you might say. But the buyer wasn’t in the room, and not even on the end of a phone, but watching the auction live through an online stream. That is, so far, the most that anybody has paid for a painting while bidding over the internet.

It was no one-off. In December 2013, Christie’s sold a work by French-Chinese painter Zao Wou-Ki called 09.05.61 for HK$13.2 million (€1.3 million) to a Chinese buyer through its online bidding platform. It was a record for an art sale in China. The drama and colour of a live auction used to be a draw, but these days even people paying millions for the finest art are opting to do it from the comfort of their own homes via a broadband connection.

It was no one-off. In December 2013, Christie’s sold a work by French-Chinese painter Zao Wou-Ki called 09.05.61 for HK$13.2 million (€1.3 million) to a Chinese buyer through its online bidding platform. It was a record for an art sale in China. The drama and colour of a live auction used to be a draw, but these days even people paying millions for the finest art are opting to do it from the comfort of their own homes via a broadband connection.

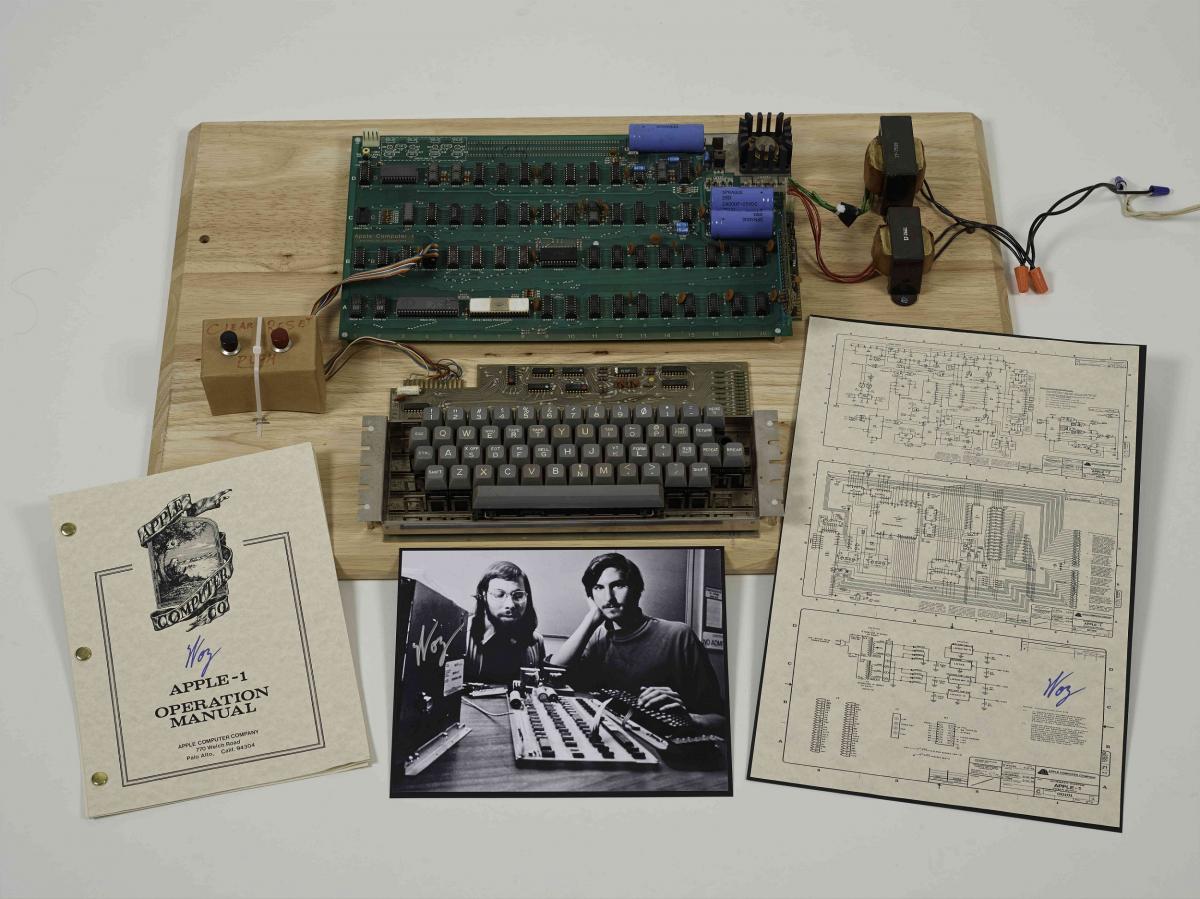

When it comes to purchasing online, buying via live-streamed auctions is not the only change. After a shaky start, online-only auctions are also taking off. Perhaps the most pleasing of these auctions so far was the sale of an original Apple computer from 1976, the so-called Apple-1 (pictured, left), which Christie’s sold for $387,750 last year. While that was eye-catching, perhaps more telling is that Christie’s had £13.2 million (€16 million) of sales from online-only auctions last year, a tenfold increase on 2012.

When it comes to purchasing online, buying via live-streamed auctions is not the only change. After a shaky start, online-only auctions are also taking off. Perhaps the most pleasing of these auctions so far was the sale of an original Apple computer from 1976, the so-called Apple-1 (pictured, left), which Christie’s sold for $387,750 last year. While that was eye-catching, perhaps more telling is that Christie’s had £13.2 million (€16 million) of sales from online-only auctions last year, a tenfold increase on 2012.

The number of online auctions they held was up from seven in 2012 to 50 in 2013. They see online as a vital way to attract new customers – 45% of buyers on the online platform were new to Christie’s, and they say that those registered to bid came from over 100 countries.

Christie’s arch-rival, Sotheby’s, is perhaps still smarting from a failed joint venture with Amazon in the early 2000s (see box page 44). It has no plans to introduce online-only auctions, although online bidding increased by 50% in 2013. Last year Amazon launched its own high-end collectibles and fine art site. It currently has more than 100 items listed ranging from $100,000 to $5 million.

The most interesting development in online buying, however, comes from beyond the oak-panelled auction rooms of the big Mayfair houses. For a number of years, a few web-based auction houses have been flourishing, such as the-saleroom.com and bidder.com in the UK, bidspotter.com in the US and lot-tissimo.com in Germany. Rather than fine art and jewels, you can buy anything on these sites from antiques to livestock, industrial machinery and toys. And that’s before you’ve even mentioned eBay.

Until now though, high-end collectibles have not made the move online. Not that they haven’t tried. As well as Sotheby’s Amazon adventure, eBay bought American auction house Butterfields in 2000, before selling it to Bonhams in 2002. But, it seems, the time may have come. An eye-catching new entrant to the market is The Auction Room, an online-only auction site run by Lucinda Blythe and George Bailey, both old Sotheby’s hands, which launched last year. It has held 14 auctions since June 2013, ranging from tribal art to jewellery, Middle Eastern contemporary art and silver, and has already built up 1,500 clients. The most popular auction so far was in October, when 112 lots were sold, attracting up to 50 bids each. (Three Wanderers in the City by Nigerian artist Twins Seven-Seven sold on the Auction Room last year, pictured right.)

Until now though, high-end collectibles have not made the move online. Not that they haven’t tried. As well as Sotheby’s Amazon adventure, eBay bought American auction house Butterfields in 2000, before selling it to Bonhams in 2002. But, it seems, the time may have come. An eye-catching new entrant to the market is The Auction Room, an online-only auction site run by Lucinda Blythe and George Bailey, both old Sotheby’s hands, which launched last year. It has held 14 auctions since June 2013, ranging from tribal art to jewellery, Middle Eastern contemporary art and silver, and has already built up 1,500 clients. The most popular auction so far was in October, when 112 lots were sold, attracting up to 50 bids each. (Three Wanderers in the City by Nigerian artist Twins Seven-Seven sold on the Auction Room last year, pictured right.)

“Online auctions had been tried before but if the Zeitgeist isn’t right they don’t work,” says Blythe from her office in Mayfair, London. There has, she acknowledges, been something of a trickle up from eBay, which has made the idea of bidding online commonplace. One of the drivers to set up the business was that the big auction houses were turning away items in the £200 to £4,000 bracket. (A stone tiki from the Marquesas Islands, pictured, left.)

“Online auctions had been tried before but if the Zeitgeist isn’t right they don’t work,” says Blythe from her office in Mayfair, London. There has, she acknowledges, been something of a trickle up from eBay, which has made the idea of bidding online commonplace. One of the drivers to set up the business was that the big auction houses were turning away items in the £200 to £4,000 bracket. (A stone tiki from the Marquesas Islands, pictured, left.)

“We perceived a gap in the mid to affordable end of the market and we thought there were efficiencies to be had,” says Blythe. “When we set up the business we thought very much that we would be in that end”. In fact, though, some have gone for higher sums. She won’t talk numbers, but one item in another sale is said to have gone for tens of thousands.

One of the benefits of being online only is that you don’t have to pay for the expensive trappings that surround the traditional auction houses – exhibition spaces in expensive places and plush surroundings. That benefits the buyer too, who doesn’t have to indirectly pay for these luxuries. “We do not have someone standing at a rostrum and there is no live auction, it is all done online,” says Blythe. (Coins On Grandma's Cloth by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, pictured, left.)

One of the benefits of being online only is that you don’t have to pay for the expensive trappings that surround the traditional auction houses – exhibition spaces in expensive places and plush surroundings. That benefits the buyer too, who doesn’t have to indirectly pay for these luxuries. “We do not have someone standing at a rostrum and there is no live auction, it is all done online,” says Blythe. (Coins On Grandma's Cloth by Ghanaian artist El Anatsui, pictured, left.)

“We normally do not print catalogues, though we did one for our African Contemporary Art sale that took place last October as it was a venture into a new market for us. Otherwise we have just uploaded all the sale items on to the site, and add the relevant notes for each item.” If needed, they can display as many images as they want of a piece, so a buyer can have a good idea of what it is like, and doesn’t have to see it in the flesh.

Another new entrant that could shake up the market is Artuner — a site selling contemporary art that was launched in October 2013. One of the founders is 26-year-old Eugenio Re Rebaudengo (pictured, left), the son of well-known Italian collector Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, and a young man steeped in the art world. As well as being surrounded by contemporary art from a young age at his family’s home and gallery in Turin, he is a member of the Tate Young Patrons Ambassador Committee, and did his university dissertation on art as an asset class.

Another new entrant that could shake up the market is Artuner — a site selling contemporary art that was launched in October 2013. One of the founders is 26-year-old Eugenio Re Rebaudengo (pictured, left), the son of well-known Italian collector Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, and a young man steeped in the art world. As well as being surrounded by contemporary art from a young age at his family’s home and gallery in Turin, he is a member of the Tate Young Patrons Ambassador Committee, and did his university dissertation on art as an asset class.

He says that, for collectors, buying online is no big deal these days. “A lot of sales from bricks and mortar galleries are done by jpeg. A lot of collectors, including my family, are not necessarily buying anymore only if we have seen the works for real. This is a clear trend that started a few years ago and is becoming more and more prominent,” he says.

There are several reasons this has happened he says, not least of which is the fact that the art world has become truly international. “What you as a collector want to do is have the best art in the world, so you are not collecting your own local artists anymore. You need to deal with the fact that artists are showing in different parts of the world. Their studios can be from the US, to South America, China, all over Europe, so the amount of time is always limited. If you want to see and get access to as much of the best art as possible you need to accept the fact that you have to rely on digital information.”

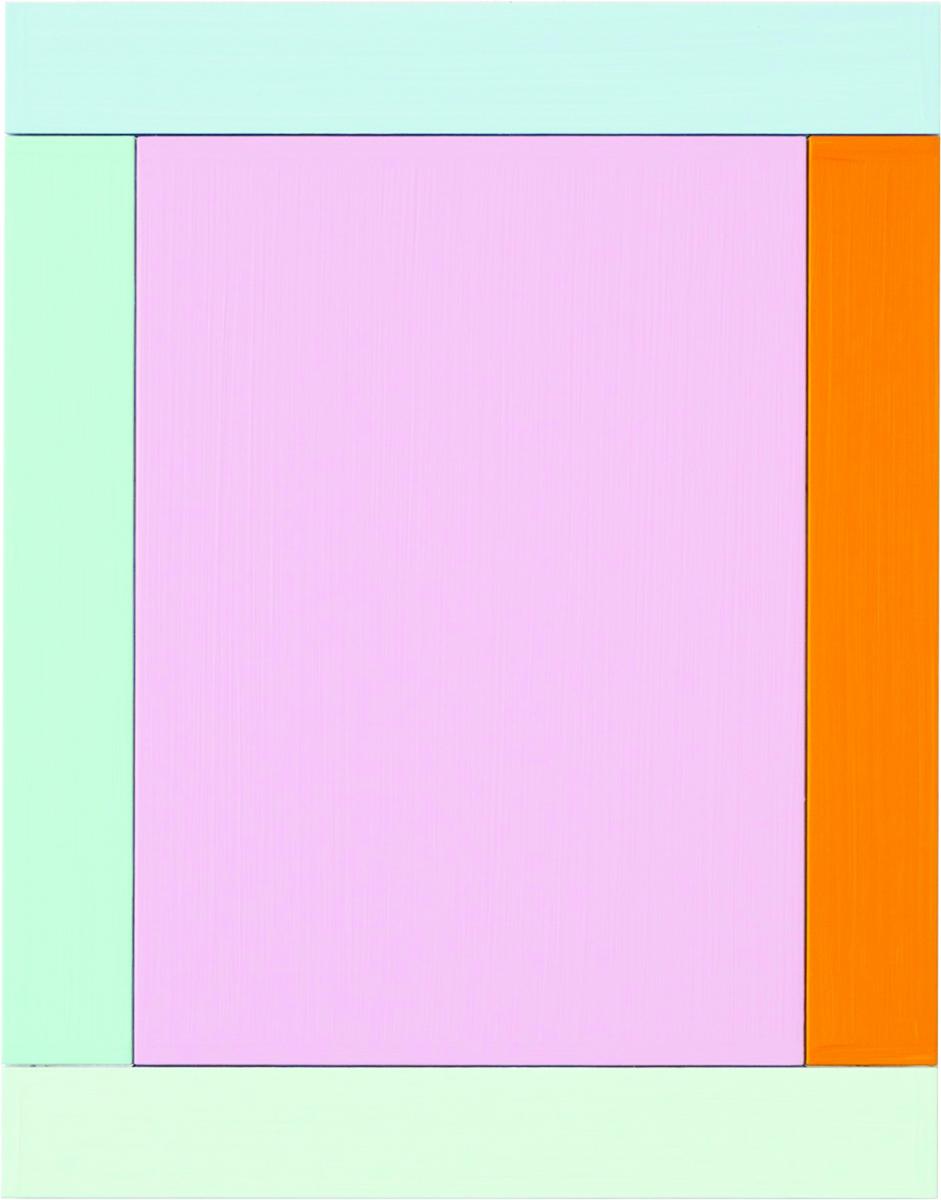

Artuner is a truly internet-age concept. For their second online “exhibition”, in January, they brought together a selection of contemporary abstract artists including well-known French and German painters Martin Barré and Imi Knoebel, and added younger ones from all over the world, including Wales and Brazil. (Anima Mundi by German artist Imi Knoebal, pictured, right.)

Artuner is a truly internet-age concept. For their second online “exhibition”, in January, they brought together a selection of contemporary abstract artists including well-known French and German painters Martin Barré and Imi Knoebel, and added younger ones from all over the world, including Wales and Brazil. (Anima Mundi by German artist Imi Knoebal, pictured, right.)

The idea is to create a “dialogue” between the works and, as Re Rebaudengo points out, bringing these artists’ works together into a physical space would be expensive, logistically difficult and time-consuming. Even once that had been done, only a small number of potential buyers could see the work. “It doesn’t make much sense to us to have one physical, permanent space in a city. It’s against the globalisation of the market,” he says. He’d rather spend time and money finding great work.

Re Rebaudengo says collectors increasingly buy objects they haven’t seen, but it beggars belief that somebody would spend £10 million on something they have not viewed, doesn’t it? Not really. Julian Roup of Bonhams, another London auction house which is seeing increasing interest in online bidding and holds online-only auctions, says that when they started selling online “we thought it would be for less valuable items, but that is no longer true. People are spending vast amounts of money. Often they want to see things in the flesh, but not always. They might have an agent who can come and see it.”

The buyer might already be familiar with a work, Roup points out, from seeing it in a museum or on tour. There really is nothing to gain from travelling thousands of miles to see it. (Bonhams recently spent £30 million revamping its London HQ, including making it easier to bid via the web – they say that 10% of bids now come online.)

The buyer might already be familiar with a work, Roup points out, from seeing it in a museum or on tour. There really is nothing to gain from travelling thousands of miles to see it. (Bonhams recently spent £30 million revamping its London HQ, including making it easier to bid via the web – they say that 10% of bids now come online.)

With some classes of items there is absolutely no need to see before you buy. Being in the same room as a case of vintage Chateau Lafite doesn’t add much to the experience of buying it. And with prints, for instance, there is no need to see them. The Auction Room is selling prints of Damien Hirst, Richter, Picasso and Chagall, among others. “Prints is a category where you can get some quite blockbuster names,” Blythe says, “and if you know the dimensions and have a good condition report then there is no need to view them.” Jewellery, says Blythe, is the only collectible that people almost always prefer to try before they buy. (Bonhams revamped HQ, pictured, left.)

One thing that connects all the successful online sellers is that buyers can trust them. They are really selling exactly the same service as the traditional auction houses – their expertise, the excellence of their curatorship and their due diligence. “The reason people feel comfortable bidding online with the major auction houses is that the thing we sell is provenance,” says Roup. “There are fakes out there and there are more in certain parts of the world. When you are dealing with us, you are getting gilt-edged assurance about the provenance; that a Warhol is a Warhol is a Warhol.”

The same is true of the likes of The Auction Room and Artuner who, despite being online, are actually closer in spirit to the gavel-bashers of Mayfair than eBay. A new law in the UK that protects buyers in online auctions won’t really affect them, as they already promise to refund works if they prove to be fake.

The trend for online buying can only grow. People are more comfortable with buying online than they were 10 years ago. Screens are also better, and jpegs give a very good idea of what a product looks like. As Re Rebaudengo says, you can see the texture of the brushwork on a painting. Online buying is also an artefact of globalisation – both sellers and buyers are everywhere.

Christie’s opened in Shanghai and Mumbai last year and says that Asian sales increased by 44%. Bonhams says it has a presence in 27 countries on five continents. That trend will only continue. Also, as Roup says, “technology itself is creating the demand. People can do anything on their tablets and phones these days, and so they want to be able to bid that way too.” With wealth spreading around the world as never before, the market for art and other valuables is becoming truly global and the demand for online buying is unstoppable. Or as Roup puts it: “It’s growing like Topsy.”

A short history of online auctions

A short history of online auctions

Back in the early, gung-ho days of the internet bubble, Sotheby’s jumped into online auctions with gusto, selling one of the 25 original copies of the Declaration of Independence online in 2000. The sale was a success, making $8.14 million, far above the guide price of $6 million. However, it pulled the plug on a 10-year deal with Amazon after just nine months, following reported losses of $100 million. For years the only auctions for high-value goods took place on eBay, culminating in 2006 when oligarch Roman Abramovich paid $168 million for a 405-ft yacht on the site.

It was not until December 2011 that Christie’s ran its first online-only auction of 973 pieces of the late actress Elizabeth Taylor’s jewellery, suggesting at the time that their hand was forced because the number of lots would have made a physical auction-room sale unwieldy.

The jewels sold for a total of $9.5 million, well over the $1 million they were expected to make. That convinced both Christie’s and Bonhams that the world was ready to do its bidding online. They were proved right. When will Sotheby’s regain its nerve?