Buy and hold?is it really that simple?

Buy good companies. And own them forever. As investment approaches go, it is seductively simple. In a financial world that often looks confused, and in places absurd, buying and holding a portfolio of high-quality companies has evident appeal. Ten years into a bull market, the approach is back in vogue. Owning high-quality equities has worked well over the past 20 years.

However, from today’s starting point—with high valuations, and a cosy consensus around the business fundamentals – these high-quality stocks look unappealing. Are these supposedly ‘safe’ stocks now, counterintuitively, one of the least attractive parts of the market?

Buy good companies. And own them forever.

As investment approaches go, it is seductively simple. In a financial world that often looks confused, and in places absurd, buying and holding a portfolio of high-quality companies has evident appeal. Ten years into a bull market, the approach is back in vogue. Owning high-quality equities has worked well over the past 20 years. However, from today’s starting point—with high valuations, and a cosy consensus around the business fundamentals – these high-quality stocks look unappealing. Are these supposedly ‘safe’ stocks now, counterintuitively, one of the least attractive parts of the market

Equities are venerated as the most attractive asset class for long-term investors – and for good reason.

The stock market and corporate entities are the best mechanism for savers to invest in the creativity and dynamism of the ideas of entrepreneurs seeking to change the world. Without the creation of equities as an investable asset, the march of human progress would have been much slower. Equities are arguably the only financial asset capable of creating transformational wealth. Over the long haul, equities have far outperformed the rest. After adjusting for inflation, £1 invested in the UK stock market in 1899 would be worth £354 today. The same £1 invested in government bonds would be worth just £5; cash, £2.50.

A bond is, in essence, a simple loan with agreed terms. A good equity, by contrast, gives a stake in a business managed (ideally) by competent, well-incentivised human beings, who can react dynamically to changing tastes, industry trends, and economic environments. At its best, we think an equity – part-ownership of a real business, run by real people, trying to solve real customer problems, with real assets – is a beautiful thing. Responsiveness matters. Levi Strauss was a young immigrant peddler in New York who moved 3,000 miles across the country to chase the opportunity offered by the California Gold Rush in 1853. He struck upon the idea of putting rivets on the seams to toughen work overalls – blue jeans were born. Levi Strauss & Co survived near destruction in the great earthquake and fires of San Francisco in 1906. From there the business and its product literally rose from the ashes to become a symbol of rebellion, romance, freedom and the American Dream.

To call on another example, in the seventeenth century Finnish company Stora Enso mined 60% of the world’s copper. Over the following 250 years, the company transitioned into iron ore and then steel. By the 1970’s, the company had evolved into renewable packaging solutions. From ancient beginnings (the company was founded in 1288), Stora Enso now has €11 billion of sales annually. Or Amazon: an investor with great imagination might have conceived that Amazon, two decades on from its initial public offering, would generate revenues of $250 billion. What they could not have imagined is that two-thirds of this online bookseller’s profits would come from something not yet in existence: so-called cloud computing, or hardware-as-a-service.

The gospel of quality investing

Every love tends to excess. Equities are no exception.

Over the past decade, devotion has grown for what we’ll call here high-quality stocks. Companies with valuable brands, strong balance sheets, recurring revenues, intellectual property, consistently high returns on invested capital with little requirement for additional investment, and a long runway of potential growth before them. We were delighted to own some of these businesses between 2008 and 2015 – Google, Johnson & Johnson, Kraft, Mondelez, Microsoft, and Lockheed Martin, among others.

Practitioners of quality-investing argue that by making a qualitative assessment of the characteristics of a business and its industry, an investor can buy good companies and essentially own them forever. The profits and growth of the underlying companies will accrue to you as a shareholder over time. In the long run, the power of these returns compounded should produce very strong performance.

Devotees of this approach believe they can identify a collection of companies with superior characteristics and enduring competitive advantages – what Warren Buffett calls “economic moats”. For this approach to work, quality-investors must believe either that these firms’ advantages are persistently underappreciated, or that they are missed entirely by others – otherwise, these superior features would be reflected in the company’s share price.

Where are the chinks in the armour?

At Ruffer, we believe a portfolio of high-quality equities is not a safe place for investors to be today – even those investors with a long time horizon. High-quality equities will not be immune to the vicissitudes of the business cycle, bear markets or inflationary regimes.

Below, we offer three points to consider

1 The macro environment matters – rising risk-free rates and inflation are a threat to all equities

2 Price paid and time both matter – valuation is as important as business quality

3 The past is not the future – historic return on equity is at best a rough guide

1. The macro environment matters

Rising risk-free rates could pose a threat to all equities. High-quality companies are particularly vulnerable, due to their high duration or ‘bond-like’ characteristics.

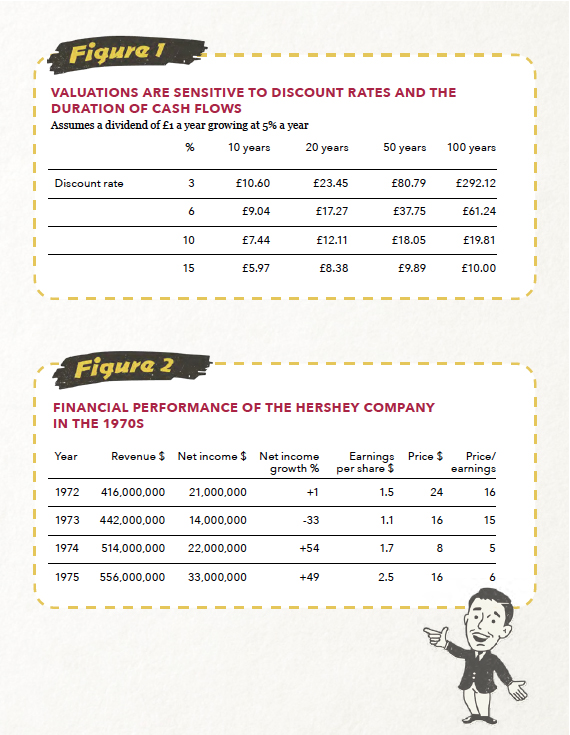

Let’s briefly step back to Financial Theory 101. Stocks are valued as the present value of all their future cash flows, discounted back to today by a required return. The valuation process requires a discount rate – typically, this is the yield on government bonds plus an equity-risk premium – with the former itself embodying risk premia to capture the inherent uncertainty around future interest rates and inflation. As Figure 1 shows, valuations are very sensitive to discount rates, and to the assumptions investors use about the length of time a cash flow will last. The effect is eye-watering. At a discount rate of 3%, a cash flow which persists for 50 years is worth almost eight times more than one which persists for 10 years – £80.79 versus £10.60.

Today, global real and nominal bond yields are at historic lows. Inflation is at multi-decade lows. Put these two together, and we can be pretty sure investors are plugging historically-low discount rates into their spreadsheets. A lower discount rate will mechanically result in a higher current share price today. What happens when interest rates rise, or inflation risk re-emerges?

With rising interest rates, the consequences are straightforward. Higher interest rates lead to higher discount rates. This – mechanically – translates to a lower present value of future cash flows all other things being equal. If the cash flows are worth less today, then a lower share price will surely follow.

Investors operate in a relative world. Savings need to be deployed somewhere. Every investment is a trade-off between risk, return and opportunity cost. When interest rates rise, all stocks look more expensively valued in a world of increasingly-attractive alternatives.

And rising inflation? Advocates of quality investing say that good businesses will be able to pass on higher costs to their customers while maintaining their strong economics. We agree. The puzzle is how the market will decide to value these businesses in a climate of rising inflation and inflation risk. Which brings us to chocolate.

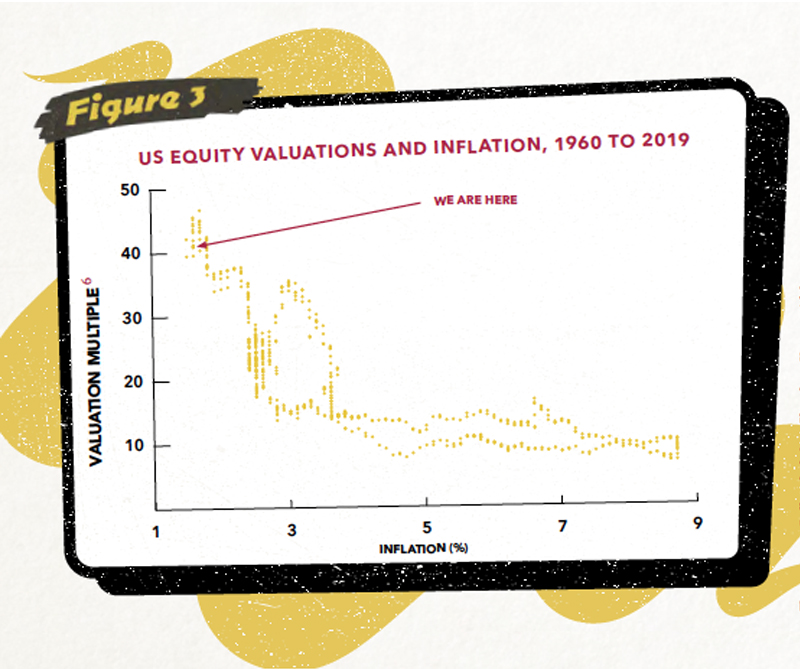

Alex Grispos, one of our Investment Directors, went into the archives and studied The Hershey Company through the inflationary environment of the 1970s. His findings are summarised in Figure 2.

As one would expect, revenues grew over the period. Net income (profits) was less stable. It fell by 33% in 1973, as there is a natural time lag between Hershey’s input costs rising and the company responding by raising prices. However, because Hershey sells products people want to eat, the company could pass-on the inflationary rise in its costs – in other words, the price increases were swallowed by customers in 1974 and 1975. Profits rose sharply in both years.

What we find fascinating is how the market decided to price the stock over this period. In 1972 investors were happy to pay $16 for $1 of Hershey earnings. By 1974, the amount they were willing to pay for a dollar of earnings had fallen to just $5. From peak to trough, the stock fell more than 60%, despite rising sales and profits.

Rising inflation tends to coincide with increasing economic uncertainty and hence rising risk premiums; leading to falling valuation multiples on stocks. As Figure 3 demonstrates, the valuation multiple for equities declines materially when inflation stops being low and stable.

When inflation becomes untethered – as we fear it might do in the years ahead – equity prices can fall sharply, echoing the experience of Hershey, as investors become unwilling to pay high valuations for each dollar of earnings. The reason investors become reticent is the much higher macroeconomic volatility and uncertainty that has always coincided with inflationary episodes. This is particularly threatening for high-quality equities starting today on elevated valuations. For example, Hershey currently trades at 27x earnings, almost double its starting valuation in 1972.

The market mood matters – we have seen this before

In the 40 years following the Great Depression, the number of Americans owning stocks rose seven-fold. By the early 1970s, the novice, everyman investor had a view on the markets, and the Nifty Fifty captured the zeitgeist.

The Nifty Fifty were a group of stocks with similar characteristics: high-quality franchises, with strong balance sheets that were benefiting from growth.

The Nifties included household favourites such as Coca-Cola, Gillette, Proctor & Gamble and Walt Disney. They were said to be one-decision stocks – buy and never sell. Many had enjoyed decades of uninterrupted growth in sales, profits and dividends.

As the darlings of the era, they became the bedrock of investor portfolios. Optimism propelled the stocks to trade on very high valuations.

Because these stocks had consistently delivered, questioning the wisdom of buying at high valuations was difficult, perhaps futile. Yet when the market mood changed the Nifties were taken out and shot one by one.

Over the next 30 years, only 10 of the Nifty Fifty outperformed the broader stock market. A number of them turned out to be booby traps: Eastman Kodak, Simplicity Patterns (sewing equipment), JC Penney and Louisiana Land & Exploration Company, amongst others.

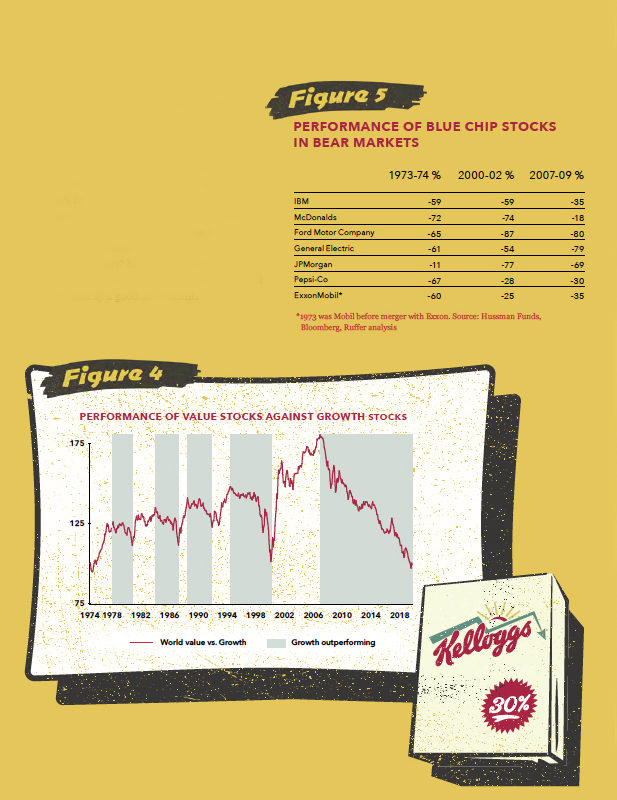

Today we see striking parallels between the original Nifties and the so-called FAANG growth stocks (Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Netflix and Google) and as other much-loved stocks with strong brands such as Unilever, Diageo, Starbucks, Visa and Microsoft. The ascendancy of these businesses is hard to challenge; their strong performance has attracted many admirers; those who don’t own them may fear they’re missing out. As Figure 4 illustrates, these growth stocks have been outperforming unloved value stocks for over a decade.

Yet from the Nifties of our generation, perhaps the first few dominoes have started to fall. Kellogg’s, Anheuser Busch, General Electric, Netflix, Kraft Heinz, FeverTree, Electronic Arts and Reckitt Benckiser have in the recent past plunged at least 30% from their highs – though some have since recovered – showing that the market consensus on the worth of these businesses can change suddenly.

The lessons? Investor exuberance can swiftly turn sour, and a good business is not necessarily a good investment.

2 Price paid and time both matter

Charlie Munger, Vice Chairman of Berkshire Hathaway, and inspiration for many investors in quality companies, put it like this in his speech in 1995:

“Over the long term it is hard for a stock to earn a much better return than the business which underlies it earns. If the business earns 6% on capital over 40 years, you are not going to make much different than a 6% return – even if you originally buy it at a huge discount. Conversely, if a business earns an 18% return on capital over 20 or 30 years, even if you pay an expensive-looking price, you’ll end up with one hell of a result.”

Our intention here is not to argue with that statement – it is factually correct – but to examine its real-world application.

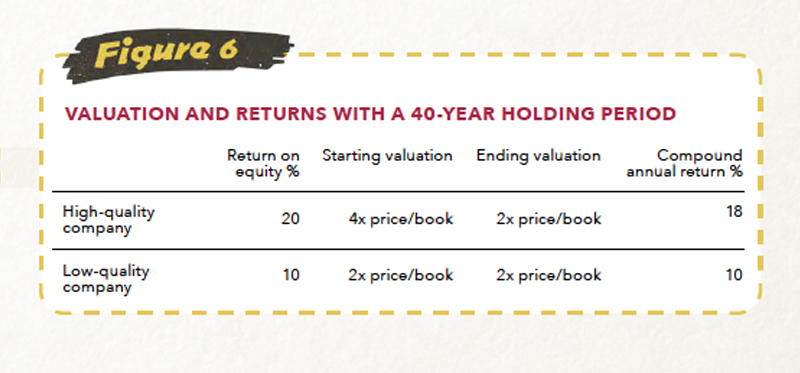

Yes, businesses earning a high return will result in better outcomes than businesses earning a low return even if the investor pays a high price for the good business. Figure 6 shows the numbers over a 40-year holding period.

Arithmetically, the numbers add up. Even with a big change in the ending valuation, the high-quality stock still outperforms by a wide margin. So much for the theory. What about the practice?

Time matters. Finding a company that can actually re-invest at 20% a year for such a long period seems close to impossible.

Take a hypothetical firm in today’s FTSE 100 index of UK stocks. If it starts with a book value of £10 billion today, and returns 20% per annum for 40 years, the company would be worth £14.7 trillion in 2060. On rough maths, that would be around 10% of the entire world’s forecast GDP. Even if a large company could grow at such a high rate for so long, it is highly likely to hit regulatory restrictions and competition issues, which would dent profitability.

If we assume that a company’s return on equity drops from 20% to 10% after five years due to emerging competition or dwindling re-investment opportunities then an investor needs to pay 25% less on day one to achieve the same total return.

What’s more, few investors have a 40-year holding period in practice. The long run is a theoretical construct; each investor only has one run.

An assumed holding period of 20 to 40 years clearly diminishes the importance of starting valuations when buying a stock. Yet the longer the holding period, the more an investor is exposed to the unpredictable and potentially damaging effects of time.

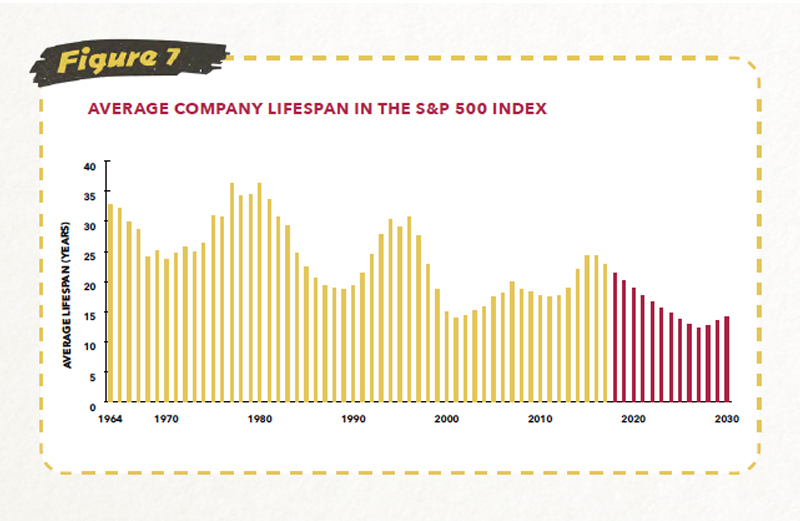

Rapid technological change means the average lifespan of a company in the S&P 500 index is now less than 20 years and falling, from an average of 30 years in the 1960s (Figure 7).

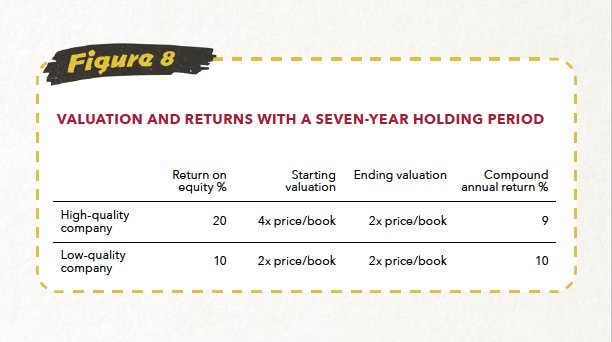

In Figure 8, we use a more realistic time frame of seven years. The returns change dramatically. Over a seven-year period, the investment in the lower-quality company delivers better performance. This is because, for the high-quality company, the impact of the fall in its valuation (de-rating) dwarfs the superior compounding of its higher return on equity. Even if the lower-quality company de-rated by 10%, the returns between the stocks would be equivalent.

Our key point here is that valuation – the price you pay – is as important as business quality. This is a point we think demands more attention.

Coca-Cola provides a good example. It is undoubtedly one of the world’s greatest brands and businesses. Say you bought the shares in 1998, when the stock traded on 50x earnings, or a 2% earnings yield. The share price fully reflected a lot of future growth. From 1998 the stock fell over 40%, and even including dividends it would have taken until 2010 for you to make money from your investment. Fast forward to 2019. After two decades as a Coca-Cola shareholder, your total return, including dividends, is only 3% a year, far less than the equivalent 7% return from the (qualitatively inferior) broad stock market and that is before inflation is considered.

3. What if the future is not like the past?

We now come to the challenge of consistent return on equity, foretelling the future, and the persistency of greatness.

There is a wonderful heuristic known as the Lindy effect which predicts the longer something has been going on, the longer it is likely to continue. As Nassim Nicholas Taleb put it: “Every year that passes without extinction doubles the additional life expectancy. This is an indicator of some robustness.” This applies to Broadway shows, marriages, the relevance of books, films or music and to the lifespans of companies.

This is important because today, high valuations are implicitly taking corporate longevity for granted. All other things being equal, it seems reasonable that longevity is an excellent predictor of future relevance but all other things are not equal.

Consider LVMH (owner of luxury brands including Louis Vuitton, Christian Dior, and Veuve Clicquot) and Diageo (Johnnie Walker, Guinness and Smirnoff, amongst others). Both LVMH and Diageo are signature high-quality stocks with brand histories often measured in centuries. Both have harnessed their intellectual property to deliver excellent returns for shareholders. A buyer of LVMH shares in 2001, re-investing their dividends, would have netted more than 14 times their initial investment (16% annualised). Similarly, buying Diageo shares in 2003 would have produced 14% annualised returns, eight times the initial investment.

Notably, throughout this period, an investor would never have been losing money on their original investment. These stocks have been a one-way ticket to investment success.

In behavioural psychology, there is a phenomenon known as the endowment effect. People become attached to things they own, and thus overvalue them. To our mind, there is a huge amount of accumulated goodwill in today’s markets – an endowment effect writ large. A generation of investors has seen a cohort of high-quality stocks deliver consistently and handsomely, regardless of the economic or market climate. At least some of this, we think a lot, must be attributable to the 30-year secular decline in interest rates rather than business fundamentals.

To us, it seems implausible that there is a quantifiable universe of stocks offering the dream combination of lower risk than the market and higher returns. For investors in LVMH and Diageo, to pick on two examples from the parish, the future may not be as bright as the past couple of decades.

A true believer might argue that these businesses possess a durability of economics and so can sustain supernormal returns – returns which under normal circumstances would be eroded by the emergence of competition. The logic being these firms have sustained a high return on equity for many years. They have some sustainable competitive advantage – an economic moat – that should allow the high returns to continue.

Two counterpoints

First, companies with seemingly unassailable advantages can be rendered redundant in a short time. Previously entrenched companies – Blockbuster Video, Thomas Cook and Yellow Pages – can become obsolete. Incumbents can be profoundly disrupted by changes, often unforeseeable, in society or technology. And brands can be tarnished, from Facebook to Boeing to Volkswagen.

Second, historic return on equity is at best a rough guide. For the future investment case, what matters is the return on the marginal new investment. Imagine that a widget factory makes a 20% return for its investors. The company then builds a second factory. To keep the company’s economics as strong, this factory also needs to produce a 20% return. It is a big leap to assume that each additional factory can continue to earn high returns without attracting competition or running up against the limits to growth.

Or consider this challenge, from a hypothetical corporate financier. If these companies can re-invest their capital at sustainable supernormal returns, why would they ever pay dividends? If you could re-invest in the business and achieve a 20% return, giving money back to shareholders would be a gross misallocation of capital!

From widgets back to Diageo. The drinks company made a 29% return on equity in 2018, down from a peak of 48% in 2009. Earnings per share appear to be growing at a far less spectacular rate: 7% a year over the past five years. This suggests dwindling re-investment opportunities. This is to be expected – Diageo has spent several decades expanding into emerging markets. Looking ahead, there are no populous continents left to conquer. Even in this halcyon era since 2001, sales have grown at just 3% a year.7 Just as trees do not grow to the sky, there are limits to the sales of premium whisky and luxury handbags.

Have investors just gone with the flow?

There is a significant body of academic evidence suggesting fund inflows follow recent strong performance. And during a 10-year bull market, quality-investing has boomed.

Ruffer’s analysis of public filings showed that some high-profile practitioners of this quality-equity approach have increased their assets under management by multiples ranging from five-fold to 36-fold since 2011.

There is a reflexive process at work. The best-performing fund managers or strategies are rewarded with greater inflows. This acts as buying support on the stocks those managers already own.

All else being equal, this will lower the volatility of the stock, pushing the manager to further outperformance. The Sharpe ratio – measuring risk-adjusted returns – will look highly attractive, drawing more investors to look at these investments.

This can sound insignificant. But while the precise impact cannot be quantified, we believe the numbers involved are considerable.

The rise of passive and factor investing has disproportionately benefitted the sort of stocks under examination here. Using data gathered by Bernstein, we estimate flows in the last few years in the region of $300 billion into factor strategies representing themes broadly defined as quality. Even these figures would be dwarfed by the huge flows into passive which are then allocated blindly to quality stocks given their considerable weightings in the relevant benchmarks. These amounts are not large in comparison to the market capitalisations of world indices, but market prices are set at the margin, and funds are flowing into a fairly narrow universe of quality and franchise stocks.

Hershey is a good example. A non-exhaustive look at Bloomberg shows this $30 billion company is owned by 161 ETFs focused on themes such as the S&P 500, dividend aristocrats, quality, brands, consumer discretionary, low-volatility, buybacks, momentum, low carbon and sustainability.

The rise of passive investing has acted as a huge tailwind to large, liquid stocks that are perceived as safe.

Investing through regimes

In conclusion, when the current benign period for financial assets comes to an end or the secular trend in interest rates reverses, the boom in quality-investing may give way to a bust. This could happen despite the underlying business fundamentals remaining solid. Great companies do not necessarily make great investments.

From today’s starting point of high valuations, and a high level of conviction that their excellence will be sustained, the forward-looking returns from these stocks look unappealing.

At Ruffer, our focus is on delivering good all-weather returns – through investment regimes, and across periods when regimes change. In our equity investments we are looking elsewhere, to industries and regions where we believe taking risk should be rewarded with attractive returns.

This article was originally published in the Ruffer Review