Born from necessity: Second-gen Ghassan Nuqul on the Nuqul Group

Seven decades ago the Nuqul family was fleeing Palestine by foot; today they head up one of Jordan's largest family businesses. Jessica Tasman-Jones spoke with its second-generation chairman about how his family business has weathered the region's geopolitical risk and the importance of good corporate governance

“My father was deprived of higher education because he did not have the means. At the time he should have been at university he was crossing the borders by foot.”

Nuqul Group second-generation vice chairman Ghassan Nuqul grew up with all the privileges of a successful entrepreneurial family, but it is his father's story that keeps the Jordanian businessman motivated.

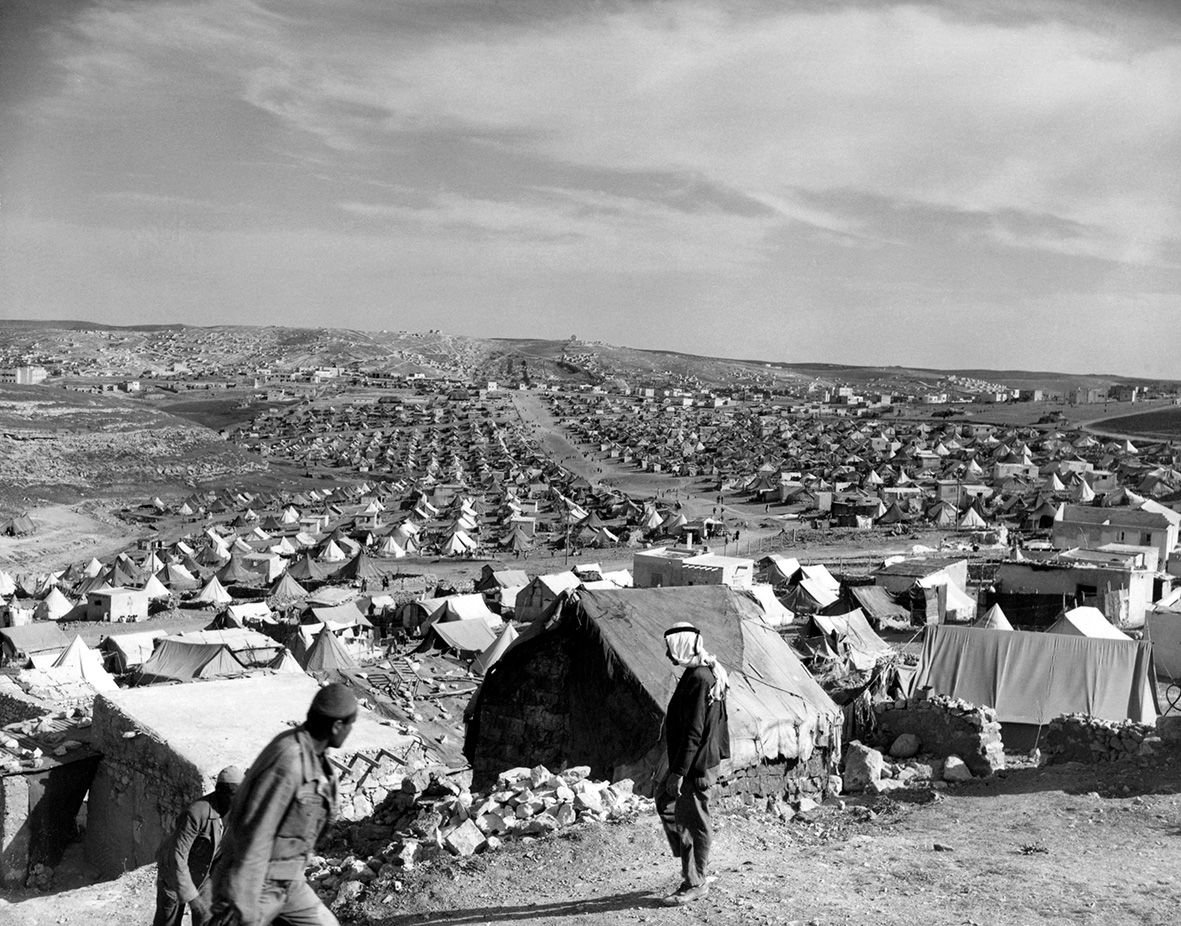

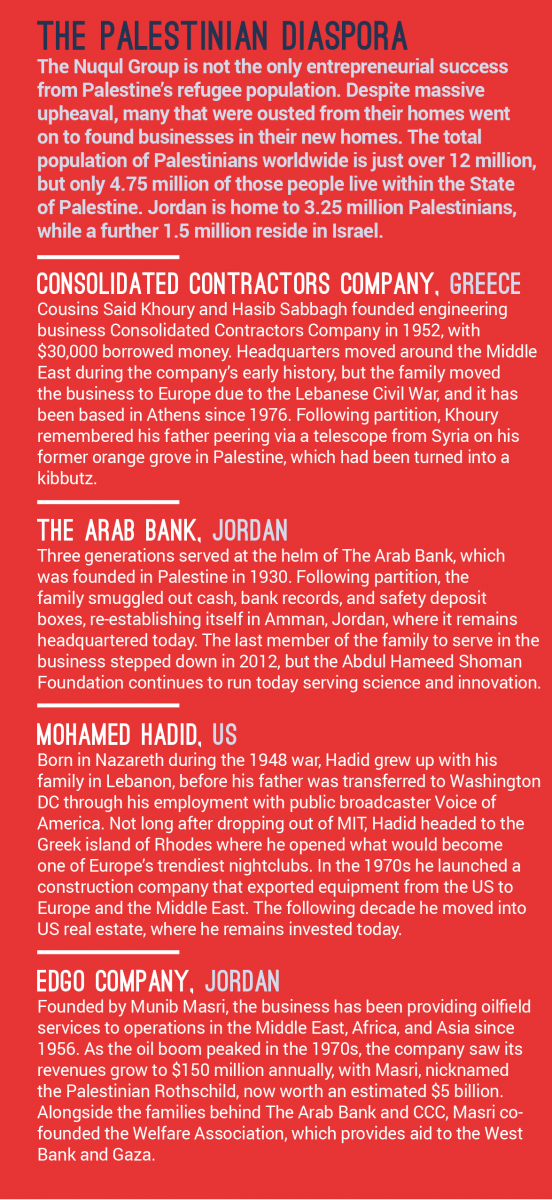

Elia Nuqul, 87, was just entering adulthood when the Palestinian exodus began. Sixty-five years later a Harvard Business School case study detailing what would become the young man's successful business career explained that he had grown up in a modest but a happy home. Elia Nuqul's father had been a greengrocer and his mother sold embroidery from their house. Less than a year after the UN Partition Plan for Palestine, Israeli forces took Ramleh, where the Christian Orthodox family lived, and they joined 400,000 refugees that fled to neighbouring Jordan, swelling its population by 40%.

Today Nuqul Group is a Middle Eastern empire, employing close to 6,000 people and reaping more than $700 million in annual revenues. In the second generation, Ghassan Nuqul is chairman of the family business, and despite his privileged upbringing, he pushes himself to do good by his family, his business, and his country, knowing how much his father struggled for the family's prosperity.

Today Nuqul Group is a Middle Eastern empire, employing close to 6,000 people and reaping more than $700 million in annual revenues. In the second generation, Ghassan Nuqul is chairman of the family business, and despite his privileged upbringing, he pushes himself to do good by his family, his business, and his country, knowing how much his father struggled for the family's prosperity.

“Success to him was not a choice,” Nuqul explains. Despite excelling academically, the Nuqul family's eviction from Ramleh coincided with the year Elia should have started tertiary education. A scholarship to study engineering at the American University in Beirut had to be turned down because it wasn't enough. “He didn't have any pocket money to buy a sandwich, let alone a t-shirt, nothing at all. He had to leave,” explains Nuqul.

Elia Nuqul suffers dementia today, but in his 2008 biography he recalled moving to Jordan and having to provide for 17 starving family members. “We lived for three years in one room without beds, only mattresses on the floor. In order to stay warm in the winter we used to put our outdoor clothes on top of our pyjamas.” Nuqul quickly found employment in Jordan, making himself indispensable to a local imports business; but it wasn't enough.

“He was determined to succeed,” Nuqul says. Already Elia had dabbled in some of his own imports: razor blades and Kiwi shoe polish. “So he started, in 1952, Nuqul Brothers Company, which basically was involved in fast-moving consumer goods, from chewing gum, to shoe polish, to playing cards, to meat, to luncheon meat, to yeast.” Among his earliest successes was a Danish chewing gum popular with children called Dandy. The next year in 1956, he introduced a tinned halal meat – Unium – to the Jordanian market.

But it would be tissue and toiletries that would really see the business take off. Investing in machinery from Germany he started to manufacture toilet paper and other toiletries. “The consumption of tissue paper was extremely low, so he priced it at 50% of what Kleenex was at to make it affordable so that people tried it and started the consumption habit. He would distribute the fine tissue pocket for free outside the movie theatres at the time so that people try them, because they were not used to it,” Nuqul said.

Success wasn't instant: there were four years of heavy losses at the subsidiary business, the Fine Hygienic Paper Company. Elia was ready to give up on the operation, but it was the image of his father – the man forced into unemployment following his eviction from Palestine – walking through the factory floor in his traditional tarboosh that revived his determination to continue with production. That same year the company made its first profit.

Success wasn't instant: there were four years of heavy losses at the subsidiary business, the Fine Hygienic Paper Company. Elia was ready to give up on the operation, but it was the image of his father – the man forced into unemployment following his eviction from Palestine – walking through the factory floor in his traditional tarboosh that revived his determination to continue with production. That same year the company made its first profit.

The family business still existed in a turbulent geopolitical environment. In 1967, the Six Day War decimated two thirds of Nuqul Brothers' market, when Israel took control of West Bank, East Jerusalem, and the Gaza Strip. Revenues had been climbing at an average annual growth rate of 124%, but dropped from $500,000 to $100,000. Elia did not dismiss a single person in his company, instead raising salaries the following year. Within months Jordan was facing another population influx with 300,000 refugees flooding the country. For the business this meant new customers seeking cheap food and supplies. By 1970, group sales were $800,000.

But again war struck. This time the Jordanian civil war with the Palestine Liberation Army. “I experienced 1948, 1967, 1970,” Elia recalled in his biography, A Promise Fulfilled. “And in all these events we were hit badly. But I remained steadfast. Everybody was afraid. I was not. I used to order more goods than normal because all the others had retreated.” Although the civil war slowed revenues at home – and saw the family move to Lebanon for 10 months – the business was expanding around the Middle East and the region's growing oil wealth bolstered revenues where war could have decimated them. As the Harvard Business Review case study on Elia Nuqul stated in 2012: “He had put his faith in business as the hope for the future of the Palestinian diaspora that lived outside the homeland which had become the state of Israel.” A decade later the family would have to temporarily suspend business in Lebanon when a shell from a local militia group hit its factory, and Ghassan's cousin was kidnapped in 1983.

Nuqul Group had five subsidiaries by the time Ghassan Nuqul joined in 1985, following undergraduate and MBA degrees in the US. His father told him he was a “partner at work, not a son”, which Nuqul admits was against Arab cultural norms. “My father wanted me to challenge the way we do business, to challenge the status quo, and he wanted us to differ, because he thought that when our ideas differ and we address them professionally the best comes out,” Nuqul explains. Traditionally, power dynamics between parents and children can be a sore point in Gulf Cooperation Council family businesses, says a report produced in 2013 by PwC, particularly during succession.

One of his most significant contributions to the family business would be its professionalisation. “I started working on documentation, institutionalisation, job descriptions, KPIs, targets, commissions, bonuses, training, vision, mission, objectives, so that we became a corporation.” The so-called Group Standard Manual became the document that guided the group. Until that point, Nuqul says the family business had been a “one-man show” – his father putting in 16 hour days doing costing, marketing, sales, buying machines, and buying materials. Over the next decade the family business would expand to 26 businesses – mostly around the Middle East.

One of his most significant contributions to the family business would be its professionalisation. “I started working on documentation, institutionalisation, job descriptions, KPIs, targets, commissions, bonuses, training, vision, mission, objectives, so that we became a corporation.” The so-called Group Standard Manual became the document that guided the group. Until that point, Nuqul says the family business had been a “one-man show” – his father putting in 16 hour days doing costing, marketing, sales, buying machines, and buying materials. Over the next decade the family business would expand to 26 businesses – mostly around the Middle East.

“The most important ingredient for success and sustainability is corporate governance,” says Nuqul. “In the family, in the business, in the public sector, in government, it is corporate governance.” As PwC points out, second and third generation companies in the Middle East are most likely to implement comprehensive corporate governance practices, whereas the first generation worries about it threatening family control. Unfortunately, those without such measures are more likely to experience conflict, especially during succession.

Good corporate governance pays financially too. Many banks in the region are shifting from lending based on personal relationships to decisions based on financial performance and balance sheets, states PwC. Nuqul agrees that banks are willing to lend at a lower rate. Additionally, he says, there is less risk in the business due to robust systems in place, and customers like buying from responsible companies. It is also more appealing to external investors, and in early 2015 Fine Hygienic Paper Company sold a 25% stake to private equity firm KKR, valued, according to Reuters, at $200 million.

“We are continuing to expand as we speak,” Nuqul says. But he adds that the company is monitoring increasing turbulence in the Middle East. “We are not blinded, we have risk management in place, and we have risk mitigation plans.” He adds that the products the business sells are important to its survival. “People are going to consume tissues, diapers, ladies toiletries, kitchen products, and they will all need banking and insurance. We are so diversified.”

Nuqul's younger brother sits on several of the company's boards, and also oversees the automotive business. Two sisters are also shareholders. Nuqul's wife also sits on the board of trustees of the family foundation, alongside his sister. A governance document stipulates the responsibilities, privileges, and duties of family members, with chapters on family council, education of the third generation, exit strategy, conflict resolution, investments, entrepreneurship, and philanthropy.

Nuqul is determined to honour his father's struggle to create a prosperous life for his family. “My father had to go singlehandedly through sacrifice, hard work, agony, and hard times.” In a personal mission statement, Nuqul has committed himself to making a difference in his family, his business, and his country. “Now the challenge I have is to translate this strong urge to make a difference to my three boys,” Nuqul says. “I want them to have enough money to survive, but not too much to be lazy. I want them to work hard, because this is how you become a better human being.”

The family foundation, the Elia Nuqul Foundation, is focused on education due to the barriers Elia Nuqul experienced trying to further himself academically as a young refugee. “My father said to himself that if and when God made him successful, he would do his part to grant access to education to as many needy people as possible.” The foundation doesn't just provide a formal education, but also works to develop students' soft skills, providing them with internships, leadership, English, community service, and IT skills. “We only ask them one condition: to pay it forward. We have a programme in the foundation that is involved in giving them the opportunity to do sustainable community service.”

The family foundation, the Elia Nuqul Foundation, is focused on education due to the barriers Elia Nuqul experienced trying to further himself academically as a young refugee. “My father said to himself that if and when God made him successful, he would do his part to grant access to education to as many needy people as possible.” The foundation doesn't just provide a formal education, but also works to develop students' soft skills, providing them with internships, leadership, English, community service, and IT skills. “We only ask them one condition: to pay it forward. We have a programme in the foundation that is involved in giving them the opportunity to do sustainable community service.”

Almost seven decades since the Nuqul family fled Palestine, Jordan suffers another influx of refugees – 600,000 have arrived since the start of the conflict in Syria in 2011. Though the family business has weathered wars and crises before, Nuqul says the Middle East's problems today are different. “First of all it is the duration of this turmoil: starting with the financial crisis; followed by the Arab Spring; and now the war with ISIS and Iraq; and the West Bank,” he says, but adds: “When you have good systems in place, good procedures, tight management, all of that, when you have turbulence you can weather it better than others.”

He says he is asked many times about the effect today of incorporating Syrian refugees into the Jordanian economy and labour force. “I tell them in the short term it's tough. However medium to long term it could create a major, huge opportunity economically for Jordan.” In February the Jordanian government had pledged to create 200,000 jobs for the incoming refugees. There is no more suitable evidence than this second generation family business of what opportunities might lay in store.